The Forgotten War - Civil War in Colombia

Social Structures, Narcotics and U.S. influence (December 2004)

by

Johan Berglund

(Political Scientist - Uppsala University - Sweden)

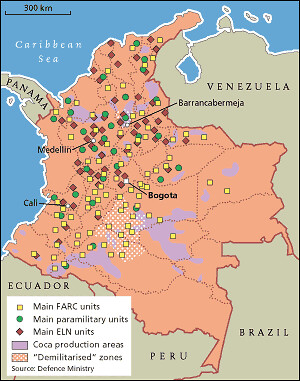

Map of Colombian Conflict as of 2002

Contents

1. Introduction

1.1 Research question

1.2 Theory: Analysing violent conflict

2. Background

2.1 Who are fighting and why?

2.2 The Civil War in Colombia: A threat to the entire region?

3. Social and political structures in a collapsing state

3.1 The State-Strength Dilemma

3.2 Social and political structures

3.3 Colombia: A Collapsing State?

4. Narcotics: the financing of a Civil War

4.1 Why in Colombia?

4.2 Social and political impact and the “war on drugs”

5. The role of the US: Ambiguous interests in Colombia’s war?

5.1 The US-Colombian relation: Hegemony and interdependence

5.2 Counter-narcotics, counter-insurgency and the “war on terrorism”

6. Conclusions

7. References

The Civil War in Colombia:

Social structures, Narcotics and U.S. influence

1. Introduction

The Civil War in Colombia has been going on for almost half a century, but still there seems to be little hope for the conflict to reach an end in the near future. And despite of its cruel nature and the many violations of Human Rights committed by all parts, the war in Colombia seems to get little attention from the outside world, compared to many other conflict areas. This is probably partly due to its elusive character and the fact that the majority of the fighting is taking place in rural and remote parts of the country.

The one country that, to a large extent, has been involved in Colombia’s bloodstained history is the US. This relationship reaches far back, and has been far from uncomplicated, as I will explore further. In this research paper I aim to look more closely on the dynamics behind the hostilities in Colombia. What are the social and political structures of the country? Who are involved and why has the conflict been so hard to come to terms with? To analyse this, I have chosen three major approaches:

# Social structures and the collapsing state

# The financing of a war: The impact of narcotics on the conflict

# The US – Colombia relation

1.1 Research question:

What are the most important dynamics behind the conflict in Colombia?

Additional questions:

Why has the conflict been so endurable? What is the role of the US in the past and current conflict and what are their main interests?

1.2 Theory: Analysing violent conflict

In every violent conflict there are a number of more or less important causes behind.

Important ones generally include: Social injustices; a low level of economic development, often linked to the degradation of renewable resources or the impact of globalization; lack of political and democratic openings; environmental degradation; and ethnic diversity. Conflicts often have both a socio-economic background as well as a political foreground, with various links between the two. As an example, a country can have a high ethnic diversity but still not experience any armed conflicts. Thus, ethnic diversity as such is not a cause of violent conflict, but rather ethnic politics, that is, if the diversity is used as a strategy for political mobilization. (Smith: 5-7)

It can hence be misleading trying to find the most important cause of a specific conflict. The question is rather how the different causes interact. It is thereby not sufficient only to look at long-term underlying causes such as the social, economic, cultural and environmental background, we need also consider the foreground, that is, politics: What are the main motives of various political actors involved? Accordingly, in armed conflicts there are background causes, mobilization strategies, but also triggers (events or actions that lit the spark) and catalysts (factors that affect the intensity and duration of the conflict). (Smith: 8-10)

By applying this analytic framework on my three main approaches, I hope to give a better understanding of the impacts behind the conflict, while considering its political foreground, triggers and catalysts.

2. Background

2.1 Who are fighting and why?

The current conflict has its roots in a very volatile period, 1947-1958, in Colombian history called ‘la Violencia’. Under a mere decade more than 200,000 people were killed and many more displaced. The instigating of the violence was the killing of the much popular politician and presidential candidate Jorge Eliécer Gaitán in April 1948. In the aftermath of this, the two major political parties, the Liberals and the Conservatives, pushed members of the two parties against the others. This inspired the madness that divided many rural towns and villages into blue and red, where supporters of one side killed or chased away their opponents. (www.icdc.com/~paulwolf/ 2002)

In 1958 the two sides eventually made an agreement to end the violence and to focus on economic development and political stability. However the agreement left many people discontented with the lack of democracy and liberal justice. This period also drew the lines for Columbia’s fractioned and diverse social and political society, consisting of many small, armed groups controlling various towns and local communities. It also set the stage for the creation of various insurgent groups. (www.peacebrigades.org 2004)

Inspired by Castro’s revolution in Cuba and disgraced over the social and political injustices in the country, the National Liberation Army (ELN) was founded in the early 1960s. During the same period, another left-wing guerrilla group was establish, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, commonly known as the FARC. These groups have since then grown bigger and approximately control and administer nearly half of Colombia’s national territory, mainly rural areas. The left-wing guerrillas have fuelled the conflict for almost four decades, profiting mainly from protection, kidnappings and later, as I will go into more closely, drug trafficking. (Sweeney 1999: 4)

Linked both to the political elites, the military, foreign and domestic landowners and corporations, as well as major drug cartels, a large, loosely connected network known as the United Self Defence Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia - AUC) operate as autonomous militia groups, protecting people with money against the guerrillas, leaving peasants and poor people defenceless. Meanwhile, the Colombian National Army has proved itself incapable of defeating the rebels. Over the last decade, most of the offensives against the guerrilla groups have failed. This development has led to a “balkanization of Colombia into politically and social unstable mini-states”, the north being controlled by paramilitary groups and drug-traffickers, the south by Marxist rebels, whereas the urban central regions, including many major cities like Bogota and Medellin, still are under government control. (Sweeney, 1999: 1)

In 1999, as an attempt to come to terms with the conflict and restore the suffering economy of the country, former President Pastrana introduced “Plan Colombia”, a US supported peace plan and anti-narcotics strategy. Trying to make peace with the rebels, the government gave extended control over large areas to the guerrilla; mainly to open up for negotiations, but these efforts seem to have had little effect in changing the course of the conflict. The FARC’s original aim was to take control over as much of the country as possible, in order to establish a Marxist Socialist regime, blaming the United States for instigating the political violence starting in the 1960s. Whether that still is the case seem to be somewhat unclear. The paramilitaries, on their side, have also rejected the peace plan, warning the government to legitimize the guerrilla and thus further destabilize the country. This has resulted in a stalemate, where neither the paramilitaries nor the rebels seem to think a peace process would gain their interests. (Sweeney 1999: 2-5)

2.2 The Civil War in Colombia: A threat to the entire region?

There is thus little sign that the conflict in Colombia is heading towards an end, but that it rather is getting worse. It clearly represents the greatest security issue in the region and, threatening to spill over into neighbouring countries, it has been growing into an issue of international destabilization and concern.

One of the neighbouring countries most involved in the Colombian crisis is Venezuela. Since the election of Hugo Chavez in 1999, the relation between the two nations has gradually deteriorated. Chavez has been known to favour the guerrillas (The Economist 2001b) and in 2001 Venezuela was accused of providing arms and sanctuary to ELN and the FARC. In the following year Colombian troops claimed to have been attacked by the FARC, entering Colombian territory from Venezuela. There has also been evidence of secret meetings between Venezuelan officials and the guerrilla. This, in return, has led the leaders of the AUC to establish fractions in Venezuela in order to cope with the new situation, which has further worsened the issue between the two neighbours. Venezuela is also the country that has the most Colombian refugees, approximately around 75,000. (Millett 2002: 7-8)

The war in Colombia also threatens other neighbouring countries. There have been reports of FARC activities in both Peru and Bolivia. In Ecuador the FARC have been involved in kidnappings as well as attacking several oil installations vital for the country’s economy. Fighting between the guerrilla and paramilitary groups has also been reported along the border as well as inside Ecuador, leading many Ecuadorians to flee from the region. At the same time, thousands of Colombian refugees cross the border to seek refuge in Ecuador, straining the countries already limited resources. (Millett 2002: 9-11)

The case of Panama is equally striking, given the country’s strategic position and the Panama Canal being crucial for international economic interests. The country has become a major arena for drug-traffickers and other crime-related groups linked to Colombia. There have also been reports on insurgents and paramilitary groups fighting in its national territory, as well as major flows of refugees into the country. While the Panamanian government has been incapable of dealing with these threats, the country has become convenient place for Guerrillas, paramilitaries and narcotics traffickers for doing business and making contacts. (Millett 2002: 11-13)

3. Social and political structures in a collapsing state

3.1 The State-Strength Dilemma

In order to analyse inter- and intrastate violent conflicts in general, it’s essential to look more closely at the social and political structures within states, as well as the strength of the states involved. State strength, in this sense, is arguably not so much a matter of military capacity, but rather about the capacity to command loyalty; that is, the right to rule. To be regarded as legitimate, the state should be able to maintain a certain degree of sovereignty; a monopoly over the legitimate use of force within a specific territory. Moreover, the state must be able to provide security and certain vital services for its citizens and to “operate within the context of a consensus-based political community”. (Holsti 1996: 82-83ff)

A common source for social tensions and internal struggle is the “poor fit” between political communities and territorial sovereignty, that is, on the one hand, the physical base of the state and on the other hand the idea and the institutional expression of the same. A totalitarian regime would hence suffer from a legitimate deficit and could therefore not be considered a strong state from this perspective. Holsti introduces two crucial aspects of legitimacy: “the principle(s) on which the ‘right to rule’ is based”, which he calls vertical legitimacy and the “sentiment of political communities” within the state, which he refers to as horizontal legitimacy. (Holsti 1996: 84)

Vertical legitimacy thus has to do with authority and consent, the rightfulness of the state and a sense of moral authority. The horizontal aspect of state legitimacy, on the other hand, would be about the attitudes and practises between various communities and groups within the state. The higher the tolerance, the more legitimate the state, so to speak. In a strong and legitimate state, no groups are excluded from economic or political power, nor can they be subject to discrimination or oppression. Hence, if “leadership commands no authority or loyalty, and a variety of groups are armed to resist those who might try to { } establish effective order”, the state has lost its legitimacy and must therefore be considered weak. (Holsti 1996: 89-90)

When looking at the Colombian case, we will see that there are many aspects that might erode the legitimacy of the state. Among these we find the (lack of) supply of essential services; inadequate allocation of resources; lack of consensus over the basic political framework; massive corruption; elite dominance; oppression and social and religious cleavages, to name some important ones. Weak states run a risk of being caught in the so called state-strength dilemma. It lacks the resources to create legitimacy by providing security and other services and might thus be tempted to adopt predatory or unlawful means in order to do so. This, of course, only further undermines its legitimacy in terms of social tensions and loyalty to the state. In addition, increased force, to keep the state together, often generates more resistance which further weakens the stare. If the state isn’t able to solve the state-strength dilemma, it is likely to be filed under the category of collapsing or failed states, with the obvious risk of civil war or interstate conflict as a consequence. (Holsti, 1996: 108-117 and 119-122)

3.2 Social and political structures

Following the period of ‘la Violencia’, the Liberal and Conservative parties would come to dominate Colombia’s political system for decades. By adopting violent means and using institutional mechanisms, popular opposition has throughout been effectively excluded from influencing the political and economic policies of the country. Instead, the dominant economic elites, mainly industrial and financial actors, have gained access to the political system through a network of interpersonal connections and institutionalized linkages. Their influence was secured by the formation of the National Front (1958-1974), which restricted political competition by excluding the left. The highly biased nature of the political system has stayed largely the same even after the formal end of the National Front in 1974, maintaining the strong traditional bonds between the political elites, the powerful economic actors and the military. As a result, a few major conglomerates, interlinked with the political elites, control the majority of the largest businesses in the country. (Avilés 2001: 34-36)

This system has brought about an increasingly neo-liberal program, favouring free-trade, privatisation and the elimination of protectionist measures. As a result of this political “stability”, through the 1980s into 1990s, Colombia’s annual growth remained considerably high, compared to many of its Latin American neighbours. Colombia was, for example, one of few countries in the region to have an international “investment-grade credit ranking”. (The Economist 2001d) But with the Lion’s share of the profits ending up in the pockets of the elites, the vast majority of the population remained poor, with unemployment rates around 20 percent. Accordingly, a wealthy minor part of the population, including major narcotic cartels, own most of the country’s profitable land. Colombian society is, in this way, socially and politically, highly stratified. (Avilés 2001: 36-37)

The rising of insurgent groups like the FARC and the ELN were much a reaction against the National Front and the concentration of political power. Among the FARC’s most important demands are: Higher social spending, the possibility for unions to take part in political and economic decision- making. The insurgents also demand a lesser influence from the US and other major corporations and investors alike; actors whose interests have often been targeted by the guerrillas. Consequently, the major priority for the military and the paramilitaries has been the defence of “national interests”, which pretty much means maintaining the political and economic hegemony of the large businesses, the landowning elites and foreign investors, mainly US. These major actors have, on the whole, been largely successful in influencing the negotiation strategies with the insurgents and the general direction of the military forces. In addition, landowners, drug traffickers and other commercial actors have financed the training and the weaponry of paramilitary groups, when the protection from the National Army proved to be inadequate. These groups accordingly grew significantly in numbers during the 1980s and 90s, notorious for their brutality against left-wing supporters and the civilian population at large. In fact, during these decades the paramilitaries were responsible for a majority of the massacres and killings taking place throughout the country. As a consequence, the government eventually felt urged to put pressure on these groups to restrict their violations of human rights. However, the government’s priorities were still not the protection of rural civilians but in “the prosecution of the drug war led by the United States”. (Avilés 2001: 38-44)

In general, social and political structures in Colombia are rooted in a deep inequality and injustices. As things have developed, these cleavages have become a basis for the conflict not to decrease. There are few functioning mechanisms for the redistribution of wealth and the inequalities in labour conditions and income are significantly high. The political vision of the insurgents may have blurred over the years, but the basis for their struggle remains. While there seem to be little belief in the overcoming of these problems by democratic procedures and reforms, violence, as a means of achieving political goals, remains a crucial element in Colombian society. In many areas this violence also reproduces itself, further eroding vital democratic and civic basis, such as freedom of speech. For the insurgents, it seems, “war remains the quickest and surest route to their political goals” while for other sectors of society, private arrangements of the defence of their interests has become essential, which accordingly weakens the strength and the legitimacy of the state. (Barón 2001: 13-17)

In addition, the economy over the last five years has suffered from a steep recession. Because of this, the conditions for everyday people have become even worse. Investments are now being somewhat held back while unemployment rates have been further increasing. (The Economist 2004d)

To conclude, the longevity of the conflict, it seems, has led to the formation on both sides of groups that have become intransigent towards the peace process, either because the war furthers their interests or because their “attitudes are [ ] too deeply rooted to change”. Some of them will most likely continue to carry out periodic campaigns of terror and “commit selective assassinations in order to impede any negotiations”. These groups, apparently, “constitute the greatest obstacle to peace”. (Baron 2001: 19)

3.3 Colombia: A Collapsing State?

Colombia has become a society where violence and conflicts have been stored up over decades, without any ability to solve them. This is mainly the result of “a social, economic and political model that has attempted to enter modernity without rejecting violence”. As a consequence of the growing fragmentation of power, the government is currently loosing its capacity to exercise sovereignty over its internal conflict. The world powers, most notably the US, have imposed the notion of “limited sovereignty” on the country, mainly concerning the issues of drug trade and human rights. The country has therefore become an object of a possible foreign intervention. If military aid is not approved, the risk of balkanization becomes urgent. On the other hand, further assistance will not guarantee the stability of the region, while it will deepen the counter-insurgency and counter-narcotics activities, and in this way also violent resistance. (Barón 2001: 27-28)

South American countries in general don’t have the multiplicity of communities found in for example ex-Yugoslavia, India or many African countries. Likewise, Colombian society is fairly consistent on basis of ethnicity, religion and language. (Holsti 1996: 153-154) On the other hand, many poor Colombians are of mixed race (Spanish, Indigenous and Africans being the main origins), which has been an obstacle to social mobility. As a consequent, many insurgents have mixed origins why joining the guerrillas has been a major social and political alternative for people from a lower background. (www.newsvote.bbc.co.uk 2004)

The nation’s violent history has also to a large degree shaped the attitudes between various communities and groups within the state, making it a regionally and socially diverse society. Large parts of the population have been effectively excluded from political and economic power and influence and discrimination and oppression of the less influential segments of society have been frequently present. Colombian society hence suffers from a deficit in horizontal legitimacy, weakening the strength of the state. The lack of democracy, openness and human and civil rights is therefore crucial aspects to keep in mind when analysing the conflict. How the interests of the various sectors of society can become more represented, is definitely a problem that has to be dealt with. (Gamboa 2001: 99-104)

As social protection no longer is provided by the central authority, but to a large extent through other arrangements, the Colombian state also suffers from a decrease in vertical legitimacy. And despite a fairly good economic development, corruption and a strong domination by the economic elites have effectively stood in the way for the redistribution of wealth and income; an allocation that could make sure that the profits from the economy would gain also the lower segments of society. Furthermore, from an international perspective the vertical legitimacy of Colombia is highly questioned. If not being able to stabilize the situation within the country, the Colombian state might become even weaker and possibly running a risk of collapsing, “which in turn could endanger the weak democracies of its Andean neighbours”. (The Economist 2001d)

To conclude, Colombian society is seemingly in a labyrinth. The state has proved incapable to provide sufficient security and other essential services for its citizens. The state’s limited capacity to exercise its sovereignty thereby becomes obvious, it being incapable to maintain a monopoly over the legitimate use of force. Leadership commands little authority and a variety of armed groups are capable to resist the establishment of effective order, especially in rural areas. Over the past decades the state has become increasingly weaker on matters of legitimacy, and in spite of a stronger military capacity, fuelled by US assistance, Colombia has not been able to solve the state-strength dilemma. The conflict has rather become frozen and, if the situation is not improved upon, Colombia apparently runs a risk of deteriorating into a so called collapsing, and even failed, state, with the possible outcome of an international intervention as an inevitable consequence.

4. Narcotics: the financing of a Civil War

In order to explain the complex and endurable nature of Colombia’s Civil War, one has to look at one of the most significant financial sources for the conflict to proceed, that is: Narcotics. As a matter of fact, drugs, mainly cocaine but also to a lesser extent heroin and marijuana, are arguably one of the most important aspects of the conflict on the whole. Since the late 1970s Colombia has remained the main cocaine producer and exporting country in the world. Generating earnings of approximately US$ 2,5 billions per year during the 1990s, cocaine constitutes around 30% of the country’s overall exports. (Zaitch 2002: 39-40) Complicating issues further, the involvement of various armed groups such as the FARC and the paramilitaries, in protection, taxation and trafficking activities, makes it one situation way beyond control for the Colombian state.

4.1 Why in Colombia?

Colombian export economy has, like many other Latin American countries, traditionally had a clear feature of short cycle ‘boom’s’ around various products at different times. During the 19th and 20th Centuries tobacco, rubber, coffee and quinine have seen such a development. However, neither of them would have such a powerful and long-lasting impact on the country as the explosive expansion of the market demand for cocaine in the early eighties. Following the so called “Cocaine wars” in Miami 1979-1982, Colombian groups took control over much of the wholesale distribution in the US, efficiently getting rid of competition from other groups, mainly Cuban and Puerto Rican. After years of savagery, a small number of Colombian illegal entrepreneurs manage to control not only the wholesale, but also production and exportation of the widely emerging drug; major ones included the Medellín Cartel and the Cali Syndicate. (www.country-studies.com 2004) There were several reasons for this: Colombian smugglers had a long tradition in illegal import-export activities, notably from marijuana trafficking in the 1960s; in Miami and New York, there were already large Colombian immigration enclaves, many of whom were willing to participate in the illegal businesses; the high level of violence used ultimately guaranteed the elimination of non-Colombian distributors; the tradition in Colombia of being a flexible short-term profiting exporting country has brought with an extensive know-how in developing foreign contacts and marketing routes and a great ability to quickly adapt production and transportation to new market requirements. (Zaitch 2002: 24-28)

The reasons why Colombia has become the major country for cocaine production and exporting are hence several, and often intertwined. Cocaine being an illegal industry, it’s important to identify the political, geographical and economic factors that have enabled it to reduce the risk of the business for the various actors involved. One important political factor is, naturally, as discussed above, the weakness of the state: Widespread corruption and a political system largely based on clientelism and patronage and a state unable to control large areas of its territory, have made it an accessible and convenient place for cocaine entrepreneurs to operate in. In addition, vital institutions in Colombian society have a long history of de-legitimization, which gradually has eroded the strength of the state. This regards the police as well as the judicial and legal systems, which have all been considerably inefficient. While other Latin America countries are also familiar with this development, neither of them have had such an extremely high level of violence as Colombia, which is one very important (difference). (Zaitch 2002: 29-30)

Furthermore, crucial geographical factors have also contributed to the development in Colombia: The country has an excellent strategic position fairly closed to the US, with “flight ranges without stopovers and good sea lines through the Caribbean”. The country has vast and remote mountainous and forest areas that make them ideal for “hiding cultivation fields, laboratories and landing strips”. (Zaitch 2002: 30)

At the time of the cocaine boom, the crisis of many regional economies got deeper. Because of the country’s neo-liberal economic policies, Colombian farmers and peasants have become highly vulnerable to the increasing competition from other world markets. Traditional crops, for example bananas, had become largely unprofitable with inflation rates increasing. As a result, coca cultivation became a reasonably safe alternative in order to maintain a relatively stable income. (Zaitch 2002: 30-31 and 47 and www.country-studies.com 2004)

The cultivation of coca doesn’t differ from that of other major crops and the processes for producing cocaine are quite simple and widely known. Production often takes place in so called “kitchen laboratories”. The relatively simple chemical and agricultural processes of producing cocaine make it highly appropriate for a less-developed country like Colombia with scarce labour skills. Furthermore, it’s not capital-intensive and demands no highly developed infrastructure. Coca cultivation and production mainly take place in rural areas with little risk of being caught. In cities or towns, small kitchens are sometimes hidden in buildings or in storehouses. (Zaitch 2002: 32-35)

Cocaine entrepreneurs come from all different groups and segments of Colombian society. Originally they derived from other illegal or legal export industries, such as marijuana smuggling or they were dealing with for example emeralds. But the accessibility of the business to enter made it attractive to upcomers and other businessmen eager to make large profits. Drug organisations were quickly established in many different regions of the country, wherever conditions were applicable basically. Different centres and organisations co-operated effectively in various national and international networks, making it heterogeneous and flexible business, including many categories of unskilled and skilled labourers, from peasants to carriers and chemists. (Zaitch 2002:40-46)

4.2 Social and political impact and the “war on drugs”

During the 1990s however, the nature of the drug industry and trafficking became more complex. This was mainly due to government policies and foreign involvement, but also the fact that the large syndicates, controlling the exports were weakened, following the killings of drug lords, such as Pablo Escobar in 1993. With the breakdown of the large cartels, new, smaller organizations popped up. Already involved in taxation (gramaje) and protection, the FARC and paramilitary groups took advantage of this power vacuum and hence become even more engaged; now also in trafficking. These new developments further strengthened the armed groups and at the same time weakened an already weak state. This of course had a large negative impact on the conflict, further deepening the social and political crisis of the country. (Thoumi 2003: 37-40)

Without doubt, the cocaine industry has had a large impact on social and political structures in Colombian society. It offers a fairly stable occupation to a wide range of groups and individuals, including peasants, workers, lawyers, pilots, financial consultants, investors, smugglers and private security to mention some. Its close links with the political elites weakens the state considerably through corruption and various violent activities. During Escobar’s war in the eighties, assassinations, threats, kidnappings, systematic murder of police officers and judges and bomb attacks were common features, which generated more violence in return from the state. Many unemployed urban youths were turned into hired killers, sicarios, by the drug gangs, making it yet another occupation promoted by the drug industry. As a matter of fact, the use of hired killers has also expanded into political and personal conflicts, further increasing the “socio-political violence” of the country. Today, Colombia has the highest murder and kidnapping rates per capita in the world. Add to this the linked terror activities and the violations of human rights committed by the paramilitaries and the FARC and it’s not difficult to see that narcotics is one of the main sources of mayhem that has been fuelling the war in Colombia over the past decades. (Zaitch 2002: 55-57 and the Economist 2004d)

The impact of the narcotics industry, domestically and regionally and its close links to left-wing guerrillas, has also made it a crucial political issue for the most powerful actor in the Western hemisphere, the United States. The widespread social damage that drugs were causing in the US in the 1970s and 80s made the Colombian cocaine industry appear to be a major threat to the American society. Initially though, the Colombian government were contented that it was the US consumers who were the actual problem and that it thereby was something for the US alone to solve. But ultimately, by offering large assistance, the US government succeeded in convincing Colombia that it had a responsibility to act. (Randall 1992: 263-264)

Today, up to approximately 90% of the cocaine and around 60% of the heroin consumed in the US each year is produced in Colombia. (http://newsvote.bbc.co.uk 2004) Together with the Colombian government, their latest answer to the situation is “Plan Colombia”; a campaign for peace and stability in order to strengthen the state and, in that way, the entire region. Initiated in 1999, the US$ 1.3 billion a year operation has mainly been focused on military assistance to strengthen the army and to promote the formation of so called “counter-narcotics” brigades, targeting notorious drug lords. Other main priorities have been assistance to the police forces and the fumigation of coca cultivating areas. (The Economist 2004d)

The policy of so called aerial spraying of coca plantings was introduced by the Pastrana administration in late 1998 and reinforced by the Uribe government in 2002. The fumigation program has been claimed by both administrations to be a success; as the total coca acreage approximately declined from about 205,000 acres down to around 173.000. However, the decline ignores important improvements in productivity. According to several reports growers have adapted new techniques, “allowing for a much greater plant density per hectare and leading to an increase in the cocaine content of the coca leaves”. Moreover, even if certain areas get sprayed, there’s never a guarantee of eradication; indeed peasants have developed methods of protecting the plants, such as preventative spraying of diluted molasses. These factors clearly undermine the significance of aerial spraying on the decrease in coca cultivating areas. (Thoumi 2003: 33-35)

Additionally, Plan Colombia is proved to have had many “unintended consequences” in the aspects of health, environmental and social impacts of fumigation and violations of human rights, committed by the army, which can also be linked to the campaign. Moreover, coca cultivation, whenever it disappears from some areas, always seems to find its way into new areas within the country and to neighbouring countries like Peru and Bolivia, but also Mexico. This makes it an intricate issue to come to terms with, in any case by using these kinds of methods. (Vaicius and Isacson 2003: 7-10)

To summarize, the escalating and endurable nature of this conflict has made it the biggest threat to the stability of the continent. The issue of narcotics clearly constitutes one its most important aspects. As a catalyst surely, the income from narcotics has all along fuelled the various actors involved and thus made it more enduring. It also strongly affects social and economic structures in Colombian society, penetrating both the state and its armed conflict, making things even more complex. Its impact on American society and connection to the left-wing guerrillas also makes it a major issue for the region’s strongest power, the United States. But before going into detail of the current US involvement in the conflict, it would be appropriate to take a closer look at the significant history of hegemony, interaction and interdependence between the two countries, without which today’s situation in Colombia, many would argue, cannot be fully understood.

5. The role of the US: Ambiguous interests in Colombia’s war?

5.1 The US-Colombian relation: Hegemony and interdependence

It seems to be impossible to explain the war in Colombia without looking closer at the country’s relation to its bigger brother, the US. Over two centuries this has been a case of close interaction and interdependence, but also of American hegemony. Since the early 20th century, the United States and Colombia have shared the culture of business expansion and economic progress; both countries often neglecting matters of political reform. Unlike the Mexican manifestations of anti-Americanism, Colombian elites have eagerly emphasized modernization rather than nationalism, making the country a convenient grow-ground for American political and economical interests. (Randall 1992: 107-9)

Major investors have included fruit companies, coffee exporters and, most importantly, oil corporations. The oil industry were established in the 1920s and since then Colombia has been a major supplier of oil to the US and worldwide, making it currently the 7th largest. And with the US intentions to reduce its dependency on supplies from the Middle East, Colombia and Venezuela have increasingly gained importance from an American perspective. (Rojas 2002: 7)

Throughout most of the 20th century strong links have been maintained between the two nations. They cooperated almost fully during World War II and their relation was clearly getting better after the Colombian distrust over the secession of Panama. The loss of Panama had since the early century been a matter of high tension between the two countries, but was gradually overcome, and during the Cold War era Colombia remained close with the US. (Randall 1992: 187-191) The fighting during ‘la Violencia’ thus, had nothing to do with international communism. Instead it was a struggle between the two major parties at the time, and Colombia needed little encouragement in supporting the anti-Soviet or the anti-Castro camp, Randall argues. It rather strengthened the relations between the two on the international stage. (Randall 1992: 218-221) Overall, US policy has been successful in the region mainly because it has served the political and economic interests of the Colombian elites. Like the major US corporations they too have benefited from the natural resources Thus, economic stability, rather than redistribution, has mainly been their interests. (Randall 1992: 260-262)

In general, US interventions in Latin America have been conducted by various reasons over the years. During the Cold War and after, protecting the continent from evil, as well as preserving the stability of the region has been the number one priority. Whether it is communism containment, narcotics or illegal immigration that’s on the agenda, has been the result of the current political and economic climate. What has come to dominate the relations between the The US and Colombia over the last couple of decades is thus a blend of three major issues: The rise of left-wing guerrilla groups such as the FARC and ELN, the enormous flow of narcotics from Colombia into the US and the threat of destabilization that the conflict constitutes to US domination in the whole region, concerning major political and economic interests. Plan Colombia is therefore arguably a mixed concern of all these issues. (Rojas 2002: 3-4, Randall 1992: 247-248)

5.2 Counter-narcotics, counter-insurgency and the “war on terrorism”

The “war on drugs” has been the most important official foil for economic aid and military assistance to Colombia since the 1980s, and by creating the term ‘narco-guerrillas, the main issues of counter-narcotics and counter-insurgency properly were given a common strategy. Since September 11, however, the concern has increasingly become a matter of anti-terrorism, labelling the groups involved ‘terrorist organisations’. Likewise, military assistance for anti-terrorism activities might as well be a matter of counter-insurgency as well as counter-narcotics. Accordingly, the Colombian government has been eagerly willing to play along in linking the war to international terrorism and groups such as Al-Quada, in order to receive the proper assistance. (Rojas 2002: 4-10 and 14)

This development allowed the Colombian government to use US military assistance in order to fight the guerrillas. In fact, since 2001, the increase in military support from the US has been somewhat around $100 million per year, mainly in weaponry and helicopters, but also for aerial spraying and it is likely to continue to rise. There has also been a recent US led campaign with the purpose to protect a crucial oil pipeline in the area of Arauca in northern Colombia. In that way, the American government is able to protect its political and economic dominance in the region without having to face heavy criticism from the international community. But unlike many other “War on terror”-countries, Colombian “terrorist” groups have long histories and are connected to a broader, intricate political and social context. Moreover, they control large amounts of territory and have their own armies with tens of thousands of fighters. Thus, transforming the conflict into an issue of counter-terrorism will probably only worsen an already dire situation, ‘fanning the flames of discontent’ among the broader population in general. (Vaicius and Isacson 2003: 11-16)

It’s a fact that the US government has been giving military aid and support to Colombia for many decades, that’s nothing new. But given the complex dynamics of this war, are more arms what is going to solve the decades-long conflict and relieve its war struck population from further suffering? One has to be asking: Who is profiting from this war and does it comply with US interests to contribute to peace?

These are of course complicated questions to answer, but none the less important. What this country needs is clearly a more peaceful and democratic society, and in order to achieve this you have to make peace an attractive thing for all parts involved. By giving military aid to the government, all that this money seems to have achieved is an escalation of the conflict, showing that the Colombian government clearly is incapable of solving its state-strength dilemma. And as a consequence of the “war on terrorism”, many of the groups involved have now lost their status as political actors, which arguably will make it more difficult to open for negotiations in the future. (Rojas 2002: 9)

Catalina Rojas, critical towards the US involvement in Colombia, argues that this “War on drugs” or “terrorism” faces a wide range of problems and must accordingly be questioned: The aid is mainly given to, and in order to cooperate with, the military sector, making it as much a support for fighting insurgents, or so called terrorists; the humanitarian and environmental costs in escalating the conflict; fumigation activities have proved inadequate in order to erase cultivation from one area without spreading it to another; the close links of paramilitary groups to certain fractions of the Colombian army makes it a risk that the aid will assist groups responsible for a majority of the violations of human rights committed in the country. (Rojas 2002: 8) As a matter of fact, the paramilitaries are reportedly responsible for a majority of the violations of human rights and the political assassinations and are therefore undeniably the biggest perpetrators of terror in Colombia. The AUC are also arguably the single biggest drug-trafficker today, accounting for about 40% of these activities. (www.zmag.org) Thus, if American aid reaches these groups, the assistance will surely worsen and prolong the conflict.

The large amounts of money given in military assistance and aerial spraying will also face other critical doubts. The most effective way to decrease coca cultivation, many would argue, would rather be by making it possible for peasants to support their living with other means, like the UN backed project “Milk for Cocaine”. Other such support could be alternative crops, cattle or a new slaughterhouse; to “send in the cows” instead of the Navy, that is. (The Economist 2004a)

Another crucial aspect of the “War on drugs” is the market. The inability to solve the drug problem inside the US, by ignoring the core problem inhabited in the market system, must not be forgotten. After all, it’s illegalization that makes cocaine profitable for the drug lords. In addition, the money being spent every year on deterring American consumers from using the drugs, as well as rehabilitation, is nowhere near of what’s being put on military assistance and fumigation in Colombia. This responsibility on the US, and Europe for that matter, is yet another aspect to consider; after all, their drug consumers are financing both the FARC and the paramilitaries, apart from the drug lords that is. (The Economist 2004b)

Overall, by focusing mainly on military assistance and other anti-drug activities while totally neglecting the civil restoration of Colombia, the US has rather worsen than improved on the conflict. Plan Colombia has merely increased the militarization in the area, without being able to cope with the narcotics issue. To keep up with their opponents, the insurgents and the paramilitaries have also felt the need to grow stronger and thus have increased their amount of criminal activities in order to further build up their armies. Written off as ‘narco-guerrillas’ and terrorists, the insurgents have also increasingly been attacking US economic investments and infrastructure, such as pipelines, as the whole situation continues in a downward spiral of violence and mistrust. At the same time, the increasing militarization has brought further restrictions on civilian powers and rights in a country where democracy was already fragile. (Rojas 2002: 9-15)

This is the reality of Colombia today, a continuing struggle with hostility, violations of human rights and crime. But the question has also to be addressed, if a peace process, as suggested by Rojas, would be likely to succeed without any major involvement from the US or the International Community, for example the UN? There are clearly those who argue that the involvements in Colombia should be even higher and that the only way to end the conflict would be my means of an international military intervention. (Sweeney 1999: 10-12) But given that Colombia is a huge country, many times the size of countries like El Salvador or Vietnam, an operation like this is not a small thing. As it is now, however, the conflict shows little sign of stagnation and Plan Colombia has been far from successful. And even if the US government really wants peace, this kind of operation would hardly gather a lot of support among the American population in general. On the other hand, the Colombian government co-operating so closely with Washington, a military intervention would seem very unlikely: As long as the US are able to wage its war in Colombia with dollar bills, to put the lives of American soldiers at stake would even seem unnecessary.

6. Conclusions

Considering my three main approaches, it becomes obvious that it’s difficult and maybe not even fruitful to look for the most important cause of conflict. In the case of Colombia many aspects interact with each other, making the conflict significantly complex and endurable. It is nevertheless possible to point out some dynamics that are maybe more important than others when trying to explain this specific case.

Looking at social and political structures, the domination by the elites is one such dynamics: Throughout the modern history of Colombia the elites have strongly dominated the political as well as the economic spheres in the country. There have been very few democratic reforms and popular opinion has been effectively left out. The economic concentration of power has left large parts of the population in poverty, despite of a relatively good economic development. This has turned Colombia into a highly stratified society, economically and politically, bringing about the rise of left-wing insurgent groups. In combination with a high level of violence and the rise of the narcotics industry, this has to a large degree shaped Colombian society.

The weakness of the state on all levels has been an important factor for the narcotics industry to grow strong and it has also created the need for private security arrangements, which was the original function of the paramilitaries. With the narcotics industry linked to the AUC and the FARC, drugs is of course one of the most important dynamics behind the conflict. Without its impact, the conflict would arguably look very different.

With a strong connection to both the Colombian elites and the drug issue, the role of the United States is also of high significance. The failure of the “war on drugs” has further contributed to worsen the situation and must overall have strong doubts about the true intentions of Washington towards the whole issue. Trade, oil, regional dominance, fighting drugs, left-wing insurgents or terrorism, the US influence on the war in Colombia must not be underestimated.

I will refrain from taking a stance towards one side or another. The three approaches I’ve chosen make an overall pattern of the conflict from which it’s possible to make various links and connections between different dynamics. Considering the approaches it seems what is being damaged is the civic society: The elites keeping a tight grip of their profits and influence seemingly without much concern for the common man. Narcotics causing violence and fear among people in general, further eroding the powers of civic society. The US meanwhile are waging its war on drugs and terrorists from above, apparently more concerned about their own economic and political influence than about the Colombian people. In the end it seems, it’s always the people that takes the hardest hit.

7. References

Books:

Social structures, Narcotics and U.S. influence

1. Introduction

The Civil War in Colombia has been going on for almost half a century, but still there seems to be little hope for the conflict to reach an end in the near future. And despite of its cruel nature and the many violations of Human Rights committed by all parts, the war in Colombia seems to get little attention from the outside world, compared to many other conflict areas. This is probably partly due to its elusive character and the fact that the majority of the fighting is taking place in rural and remote parts of the country.

The one country that, to a large extent, has been involved in Colombia’s bloodstained history is the US. This relationship reaches far back, and has been far from uncomplicated, as I will explore further. In this research paper I aim to look more closely on the dynamics behind the hostilities in Colombia. What are the social and political structures of the country? Who are involved and why has the conflict been so hard to come to terms with? To analyse this, I have chosen three major approaches:

# Social structures and the collapsing state

# The financing of a war: The impact of narcotics on the conflict

# The US – Colombia relation

1.1 Research question:

What are the most important dynamics behind the conflict in Colombia?

Additional questions:

Why has the conflict been so endurable? What is the role of the US in the past and current conflict and what are their main interests?

1.2 Theory: Analysing violent conflict

In every violent conflict there are a number of more or less important causes behind.

Important ones generally include: Social injustices; a low level of economic development, often linked to the degradation of renewable resources or the impact of globalization; lack of political and democratic openings; environmental degradation; and ethnic diversity. Conflicts often have both a socio-economic background as well as a political foreground, with various links between the two. As an example, a country can have a high ethnic diversity but still not experience any armed conflicts. Thus, ethnic diversity as such is not a cause of violent conflict, but rather ethnic politics, that is, if the diversity is used as a strategy for political mobilization. (Smith: 5-7)

It can hence be misleading trying to find the most important cause of a specific conflict. The question is rather how the different causes interact. It is thereby not sufficient only to look at long-term underlying causes such as the social, economic, cultural and environmental background, we need also consider the foreground, that is, politics: What are the main motives of various political actors involved? Accordingly, in armed conflicts there are background causes, mobilization strategies, but also triggers (events or actions that lit the spark) and catalysts (factors that affect the intensity and duration of the conflict). (Smith: 8-10)

By applying this analytic framework on my three main approaches, I hope to give a better understanding of the impacts behind the conflict, while considering its political foreground, triggers and catalysts.

2. Background

2.1 Who are fighting and why?

The current conflict has its roots in a very volatile period, 1947-1958, in Colombian history called ‘la Violencia’. Under a mere decade more than 200,000 people were killed and many more displaced. The instigating of the violence was the killing of the much popular politician and presidential candidate Jorge Eliécer Gaitán in April 1948. In the aftermath of this, the two major political parties, the Liberals and the Conservatives, pushed members of the two parties against the others. This inspired the madness that divided many rural towns and villages into blue and red, where supporters of one side killed or chased away their opponents. (www.icdc.com/~paulwolf/ 2002)

In 1958 the two sides eventually made an agreement to end the violence and to focus on economic development and political stability. However the agreement left many people discontented with the lack of democracy and liberal justice. This period also drew the lines for Columbia’s fractioned and diverse social and political society, consisting of many small, armed groups controlling various towns and local communities. It also set the stage for the creation of various insurgent groups. (www.peacebrigades.org 2004)

Inspired by Castro’s revolution in Cuba and disgraced over the social and political injustices in the country, the National Liberation Army (ELN) was founded in the early 1960s. During the same period, another left-wing guerrilla group was establish, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, commonly known as the FARC. These groups have since then grown bigger and approximately control and administer nearly half of Colombia’s national territory, mainly rural areas. The left-wing guerrillas have fuelled the conflict for almost four decades, profiting mainly from protection, kidnappings and later, as I will go into more closely, drug trafficking. (Sweeney 1999: 4)

Linked both to the political elites, the military, foreign and domestic landowners and corporations, as well as major drug cartels, a large, loosely connected network known as the United Self Defence Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia - AUC) operate as autonomous militia groups, protecting people with money against the guerrillas, leaving peasants and poor people defenceless. Meanwhile, the Colombian National Army has proved itself incapable of defeating the rebels. Over the last decade, most of the offensives against the guerrilla groups have failed. This development has led to a “balkanization of Colombia into politically and social unstable mini-states”, the north being controlled by paramilitary groups and drug-traffickers, the south by Marxist rebels, whereas the urban central regions, including many major cities like Bogota and Medellin, still are under government control. (Sweeney, 1999: 1)

In 1999, as an attempt to come to terms with the conflict and restore the suffering economy of the country, former President Pastrana introduced “Plan Colombia”, a US supported peace plan and anti-narcotics strategy. Trying to make peace with the rebels, the government gave extended control over large areas to the guerrilla; mainly to open up for negotiations, but these efforts seem to have had little effect in changing the course of the conflict. The FARC’s original aim was to take control over as much of the country as possible, in order to establish a Marxist Socialist regime, blaming the United States for instigating the political violence starting in the 1960s. Whether that still is the case seem to be somewhat unclear. The paramilitaries, on their side, have also rejected the peace plan, warning the government to legitimize the guerrilla and thus further destabilize the country. This has resulted in a stalemate, where neither the paramilitaries nor the rebels seem to think a peace process would gain their interests. (Sweeney 1999: 2-5)

2.2 The Civil War in Colombia: A threat to the entire region?

There is thus little sign that the conflict in Colombia is heading towards an end, but that it rather is getting worse. It clearly represents the greatest security issue in the region and, threatening to spill over into neighbouring countries, it has been growing into an issue of international destabilization and concern.

One of the neighbouring countries most involved in the Colombian crisis is Venezuela. Since the election of Hugo Chavez in 1999, the relation between the two nations has gradually deteriorated. Chavez has been known to favour the guerrillas (The Economist 2001b) and in 2001 Venezuela was accused of providing arms and sanctuary to ELN and the FARC. In the following year Colombian troops claimed to have been attacked by the FARC, entering Colombian territory from Venezuela. There has also been evidence of secret meetings between Venezuelan officials and the guerrilla. This, in return, has led the leaders of the AUC to establish fractions in Venezuela in order to cope with the new situation, which has further worsened the issue between the two neighbours. Venezuela is also the country that has the most Colombian refugees, approximately around 75,000. (Millett 2002: 7-8)

The war in Colombia also threatens other neighbouring countries. There have been reports of FARC activities in both Peru and Bolivia. In Ecuador the FARC have been involved in kidnappings as well as attacking several oil installations vital for the country’s economy. Fighting between the guerrilla and paramilitary groups has also been reported along the border as well as inside Ecuador, leading many Ecuadorians to flee from the region. At the same time, thousands of Colombian refugees cross the border to seek refuge in Ecuador, straining the countries already limited resources. (Millett 2002: 9-11)

The case of Panama is equally striking, given the country’s strategic position and the Panama Canal being crucial for international economic interests. The country has become a major arena for drug-traffickers and other crime-related groups linked to Colombia. There have also been reports on insurgents and paramilitary groups fighting in its national territory, as well as major flows of refugees into the country. While the Panamanian government has been incapable of dealing with these threats, the country has become convenient place for Guerrillas, paramilitaries and narcotics traffickers for doing business and making contacts. (Millett 2002: 11-13)

3. Social and political structures in a collapsing state

3.1 The State-Strength Dilemma

In order to analyse inter- and intrastate violent conflicts in general, it’s essential to look more closely at the social and political structures within states, as well as the strength of the states involved. State strength, in this sense, is arguably not so much a matter of military capacity, but rather about the capacity to command loyalty; that is, the right to rule. To be regarded as legitimate, the state should be able to maintain a certain degree of sovereignty; a monopoly over the legitimate use of force within a specific territory. Moreover, the state must be able to provide security and certain vital services for its citizens and to “operate within the context of a consensus-based political community”. (Holsti 1996: 82-83ff)

A common source for social tensions and internal struggle is the “poor fit” between political communities and territorial sovereignty, that is, on the one hand, the physical base of the state and on the other hand the idea and the institutional expression of the same. A totalitarian regime would hence suffer from a legitimate deficit and could therefore not be considered a strong state from this perspective. Holsti introduces two crucial aspects of legitimacy: “the principle(s) on which the ‘right to rule’ is based”, which he calls vertical legitimacy and the “sentiment of political communities” within the state, which he refers to as horizontal legitimacy. (Holsti 1996: 84)

Vertical legitimacy thus has to do with authority and consent, the rightfulness of the state and a sense of moral authority. The horizontal aspect of state legitimacy, on the other hand, would be about the attitudes and practises between various communities and groups within the state. The higher the tolerance, the more legitimate the state, so to speak. In a strong and legitimate state, no groups are excluded from economic or political power, nor can they be subject to discrimination or oppression. Hence, if “leadership commands no authority or loyalty, and a variety of groups are armed to resist those who might try to { } establish effective order”, the state has lost its legitimacy and must therefore be considered weak. (Holsti 1996: 89-90)

When looking at the Colombian case, we will see that there are many aspects that might erode the legitimacy of the state. Among these we find the (lack of) supply of essential services; inadequate allocation of resources; lack of consensus over the basic political framework; massive corruption; elite dominance; oppression and social and religious cleavages, to name some important ones. Weak states run a risk of being caught in the so called state-strength dilemma. It lacks the resources to create legitimacy by providing security and other services and might thus be tempted to adopt predatory or unlawful means in order to do so. This, of course, only further undermines its legitimacy in terms of social tensions and loyalty to the state. In addition, increased force, to keep the state together, often generates more resistance which further weakens the stare. If the state isn’t able to solve the state-strength dilemma, it is likely to be filed under the category of collapsing or failed states, with the obvious risk of civil war or interstate conflict as a consequence. (Holsti, 1996: 108-117 and 119-122)

3.2 Social and political structures

Following the period of ‘la Violencia’, the Liberal and Conservative parties would come to dominate Colombia’s political system for decades. By adopting violent means and using institutional mechanisms, popular opposition has throughout been effectively excluded from influencing the political and economic policies of the country. Instead, the dominant economic elites, mainly industrial and financial actors, have gained access to the political system through a network of interpersonal connections and institutionalized linkages. Their influence was secured by the formation of the National Front (1958-1974), which restricted political competition by excluding the left. The highly biased nature of the political system has stayed largely the same even after the formal end of the National Front in 1974, maintaining the strong traditional bonds between the political elites, the powerful economic actors and the military. As a result, a few major conglomerates, interlinked with the political elites, control the majority of the largest businesses in the country. (Avilés 2001: 34-36)

This system has brought about an increasingly neo-liberal program, favouring free-trade, privatisation and the elimination of protectionist measures. As a result of this political “stability”, through the 1980s into 1990s, Colombia’s annual growth remained considerably high, compared to many of its Latin American neighbours. Colombia was, for example, one of few countries in the region to have an international “investment-grade credit ranking”. (The Economist 2001d) But with the Lion’s share of the profits ending up in the pockets of the elites, the vast majority of the population remained poor, with unemployment rates around 20 percent. Accordingly, a wealthy minor part of the population, including major narcotic cartels, own most of the country’s profitable land. Colombian society is, in this way, socially and politically, highly stratified. (Avilés 2001: 36-37)

The rising of insurgent groups like the FARC and the ELN were much a reaction against the National Front and the concentration of political power. Among the FARC’s most important demands are: Higher social spending, the possibility for unions to take part in political and economic decision- making. The insurgents also demand a lesser influence from the US and other major corporations and investors alike; actors whose interests have often been targeted by the guerrillas. Consequently, the major priority for the military and the paramilitaries has been the defence of “national interests”, which pretty much means maintaining the political and economic hegemony of the large businesses, the landowning elites and foreign investors, mainly US. These major actors have, on the whole, been largely successful in influencing the negotiation strategies with the insurgents and the general direction of the military forces. In addition, landowners, drug traffickers and other commercial actors have financed the training and the weaponry of paramilitary groups, when the protection from the National Army proved to be inadequate. These groups accordingly grew significantly in numbers during the 1980s and 90s, notorious for their brutality against left-wing supporters and the civilian population at large. In fact, during these decades the paramilitaries were responsible for a majority of the massacres and killings taking place throughout the country. As a consequence, the government eventually felt urged to put pressure on these groups to restrict their violations of human rights. However, the government’s priorities were still not the protection of rural civilians but in “the prosecution of the drug war led by the United States”. (Avilés 2001: 38-44)

In general, social and political structures in Colombia are rooted in a deep inequality and injustices. As things have developed, these cleavages have become a basis for the conflict not to decrease. There are few functioning mechanisms for the redistribution of wealth and the inequalities in labour conditions and income are significantly high. The political vision of the insurgents may have blurred over the years, but the basis for their struggle remains. While there seem to be little belief in the overcoming of these problems by democratic procedures and reforms, violence, as a means of achieving political goals, remains a crucial element in Colombian society. In many areas this violence also reproduces itself, further eroding vital democratic and civic basis, such as freedom of speech. For the insurgents, it seems, “war remains the quickest and surest route to their political goals” while for other sectors of society, private arrangements of the defence of their interests has become essential, which accordingly weakens the strength and the legitimacy of the state. (Barón 2001: 13-17)

In addition, the economy over the last five years has suffered from a steep recession. Because of this, the conditions for everyday people have become even worse. Investments are now being somewhat held back while unemployment rates have been further increasing. (The Economist 2004d)

To conclude, the longevity of the conflict, it seems, has led to the formation on both sides of groups that have become intransigent towards the peace process, either because the war furthers their interests or because their “attitudes are [ ] too deeply rooted to change”. Some of them will most likely continue to carry out periodic campaigns of terror and “commit selective assassinations in order to impede any negotiations”. These groups, apparently, “constitute the greatest obstacle to peace”. (Baron 2001: 19)

3.3 Colombia: A Collapsing State?

Colombia has become a society where violence and conflicts have been stored up over decades, without any ability to solve them. This is mainly the result of “a social, economic and political model that has attempted to enter modernity without rejecting violence”. As a consequence of the growing fragmentation of power, the government is currently loosing its capacity to exercise sovereignty over its internal conflict. The world powers, most notably the US, have imposed the notion of “limited sovereignty” on the country, mainly concerning the issues of drug trade and human rights. The country has therefore become an object of a possible foreign intervention. If military aid is not approved, the risk of balkanization becomes urgent. On the other hand, further assistance will not guarantee the stability of the region, while it will deepen the counter-insurgency and counter-narcotics activities, and in this way also violent resistance. (Barón 2001: 27-28)

South American countries in general don’t have the multiplicity of communities found in for example ex-Yugoslavia, India or many African countries. Likewise, Colombian society is fairly consistent on basis of ethnicity, religion and language. (Holsti 1996: 153-154) On the other hand, many poor Colombians are of mixed race (Spanish, Indigenous and Africans being the main origins), which has been an obstacle to social mobility. As a consequent, many insurgents have mixed origins why joining the guerrillas has been a major social and political alternative for people from a lower background. (www.newsvote.bbc.co.uk 2004)

The nation’s violent history has also to a large degree shaped the attitudes between various communities and groups within the state, making it a regionally and socially diverse society. Large parts of the population have been effectively excluded from political and economic power and influence and discrimination and oppression of the less influential segments of society have been frequently present. Colombian society hence suffers from a deficit in horizontal legitimacy, weakening the strength of the state. The lack of democracy, openness and human and civil rights is therefore crucial aspects to keep in mind when analysing the conflict. How the interests of the various sectors of society can become more represented, is definitely a problem that has to be dealt with. (Gamboa 2001: 99-104)

As social protection no longer is provided by the central authority, but to a large extent through other arrangements, the Colombian state also suffers from a decrease in vertical legitimacy. And despite a fairly good economic development, corruption and a strong domination by the economic elites have effectively stood in the way for the redistribution of wealth and income; an allocation that could make sure that the profits from the economy would gain also the lower segments of society. Furthermore, from an international perspective the vertical legitimacy of Colombia is highly questioned. If not being able to stabilize the situation within the country, the Colombian state might become even weaker and possibly running a risk of collapsing, “which in turn could endanger the weak democracies of its Andean neighbours”. (The Economist 2001d)

To conclude, Colombian society is seemingly in a labyrinth. The state has proved incapable to provide sufficient security and other essential services for its citizens. The state’s limited capacity to exercise its sovereignty thereby becomes obvious, it being incapable to maintain a monopoly over the legitimate use of force. Leadership commands little authority and a variety of armed groups are capable to resist the establishment of effective order, especially in rural areas. Over the past decades the state has become increasingly weaker on matters of legitimacy, and in spite of a stronger military capacity, fuelled by US assistance, Colombia has not been able to solve the state-strength dilemma. The conflict has rather become frozen and, if the situation is not improved upon, Colombia apparently runs a risk of deteriorating into a so called collapsing, and even failed, state, with the possible outcome of an international intervention as an inevitable consequence.

4. Narcotics: the financing of a Civil War

In order to explain the complex and endurable nature of Colombia’s Civil War, one has to look at one of the most significant financial sources for the conflict to proceed, that is: Narcotics. As a matter of fact, drugs, mainly cocaine but also to a lesser extent heroin and marijuana, are arguably one of the most important aspects of the conflict on the whole. Since the late 1970s Colombia has remained the main cocaine producer and exporting country in the world. Generating earnings of approximately US$ 2,5 billions per year during the 1990s, cocaine constitutes around 30% of the country’s overall exports. (Zaitch 2002: 39-40) Complicating issues further, the involvement of various armed groups such as the FARC and the paramilitaries, in protection, taxation and trafficking activities, makes it one situation way beyond control for the Colombian state.

4.1 Why in Colombia?

Colombian export economy has, like many other Latin American countries, traditionally had a clear feature of short cycle ‘boom’s’ around various products at different times. During the 19th and 20th Centuries tobacco, rubber, coffee and quinine have seen such a development. However, neither of them would have such a powerful and long-lasting impact on the country as the explosive expansion of the market demand for cocaine in the early eighties. Following the so called “Cocaine wars” in Miami 1979-1982, Colombian groups took control over much of the wholesale distribution in the US, efficiently getting rid of competition from other groups, mainly Cuban and Puerto Rican. After years of savagery, a small number of Colombian illegal entrepreneurs manage to control not only the wholesale, but also production and exportation of the widely emerging drug; major ones included the Medellín Cartel and the Cali Syndicate. (www.country-studies.com 2004) There were several reasons for this: Colombian smugglers had a long tradition in illegal import-export activities, notably from marijuana trafficking in the 1960s; in Miami and New York, there were already large Colombian immigration enclaves, many of whom were willing to participate in the illegal businesses; the high level of violence used ultimately guaranteed the elimination of non-Colombian distributors; the tradition in Colombia of being a flexible short-term profiting exporting country has brought with an extensive know-how in developing foreign contacts and marketing routes and a great ability to quickly adapt production and transportation to new market requirements. (Zaitch 2002: 24-28)

The reasons why Colombia has become the major country for cocaine production and exporting are hence several, and often intertwined. Cocaine being an illegal industry, it’s important to identify the political, geographical and economic factors that have enabled it to reduce the risk of the business for the various actors involved. One important political factor is, naturally, as discussed above, the weakness of the state: Widespread corruption and a political system largely based on clientelism and patronage and a state unable to control large areas of its territory, have made it an accessible and convenient place for cocaine entrepreneurs to operate in. In addition, vital institutions in Colombian society have a long history of de-legitimization, which gradually has eroded the strength of the state. This regards the police as well as the judicial and legal systems, which have all been considerably inefficient. While other Latin America countries are also familiar with this development, neither of them have had such an extremely high level of violence as Colombia, which is one very important (difference). (Zaitch 2002: 29-30)

Furthermore, crucial geographical factors have also contributed to the development in Colombia: The country has an excellent strategic position fairly closed to the US, with “flight ranges without stopovers and good sea lines through the Caribbean”. The country has vast and remote mountainous and forest areas that make them ideal for “hiding cultivation fields, laboratories and landing strips”. (Zaitch 2002: 30)

At the time of the cocaine boom, the crisis of many regional economies got deeper. Because of the country’s neo-liberal economic policies, Colombian farmers and peasants have become highly vulnerable to the increasing competition from other world markets. Traditional crops, for example bananas, had become largely unprofitable with inflation rates increasing. As a result, coca cultivation became a reasonably safe alternative in order to maintain a relatively stable income. (Zaitch 2002: 30-31 and 47 and www.country-studies.com 2004)

The cultivation of coca doesn’t differ from that of other major crops and the processes for producing cocaine are quite simple and widely known. Production often takes place in so called “kitchen laboratories”. The relatively simple chemical and agricultural processes of producing cocaine make it highly appropriate for a less-developed country like Colombia with scarce labour skills. Furthermore, it’s not capital-intensive and demands no highly developed infrastructure. Coca cultivation and production mainly take place in rural areas with little risk of being caught. In cities or towns, small kitchens are sometimes hidden in buildings or in storehouses. (Zaitch 2002: 32-35)