The Internet: Between Commerce and Culture - Final Portfolio

1) Riding the third wave (Week 2: a Response)

Spaces unplugged from the network will suddenly increase their value because they will become scarcer. People will do strange things and long travellings to get there. Out of the network. That might be a kind of hope for the fourth world. The pleasure of being unpplugged. Here a text about that pleasure which I experienced deep into the Amazon jungle:

Under the Milky Way (of the Amazonian Rainforest - of the Amazon River)

The days went on. Subtle wake up calls from carpenter birds on a dry tree. Early morning love and sweat. Natural breakfast from the soil. Heat and heat again under the rain. Pendulums of embraced bodies, hammocks, lingering, and juices of new fruits. Long walks penetrating deep into the humid welcoming forest. Traces of animals avoiding humans for a reason. Birds singing to each other about the strange travellers and flying over our heads. An eagle hunting in circles. The ¿ghost tiger¿ lake and its stolen virgins shinning under a perpendicular sun. Sounds of steps on skeletons of gigantic fallen leaves. Marks of native pain on crying rubber trees. Salty eyes of water for the pleasure of hidden bears and jaguars. Heavy raindrops, shadowed jungle, fresh air. Fished purple diamond glittering piranhas hanging and released again. Mosquitoes but no people or cars or noise. The friendly erudite native guide and his beautiful dreamy wife. Small communities of men and women living in reality, with other simple lives, other worlds, other words, along an ancient river without the bad news of the west. A thousand year-old tree flowering green at the top of its giant trunk watching the equator every summer forever. Our rapt eyes, up there, against a mythical green ocean of trees and a hiding disc of gold saying goodbye from the horizon. The different sounds and creatures of the night, the hidden red eyes of small, playful caimans, a singing calmed Shaman, a sacred drink and spirals of dreams. Visions of unseen animals and lived memories, a cradle of ancient songs and mixed, caring words, innocent again for a second, hand on a woman¿s hand. Laying back against the side of the peque*, the moving river touching our hair, we watched the stars and the moonset and the powerful silver belt of the Milky Way. That green ocean sunset and those lucid stars, with me until the day I die.

July 2004 (from "memories" of October 2003).

* Peque: small boat used for short distances in the Amazon region.

====================

2) Is personal identity possible in Cyberspace? (Week 6: a Contribution)

"Who speaks?" asks Foucault. Who cares seems to be the answer (although Microsoft and the White House do still care, and also some other friends of theirs that enjoy the same golf courts and summer afternoons). Mark Poster relates this Foucauldian question to new preoccupations with links, associations, and dispersions of meaning throughout the web of discourse (p. 68). Poster¿s differentiation between digital authors and analogue authors, as he acknowledges, is embedded, starting with the use of the words digital and analogue, by the centrality of the machinic mediation that conditions late modernity relationships between so-called humans.

With this context in mind the issue of postmodern identities as mediated projects can be understood as the transition from a located-analogue author to a new dispersed-multiple-digital author, inexistent as an "authority," inexistent as a celebrity, but murmuring bricollaged texts through the invisible wires of the Internet. Everyone with access to the Internet is a digital author, with certain materials available, with certain symbols and skills at "reach distance". This new author's multiple-dispersed-digital links and associations, will show who he or she is and where he or she comes from or wants to go. The author¿s identity will be expressed in the form of a collage of interests and organizations to which he or she has been related. While co-presence diminishes in importance, the expression of identity for individuals with access to ICTs becomes more and more a mediated project, even multiple projects; from post, to telegraph, to telephone, to mobile phones, to a network of multiple contacts, multiple projected identities can be built, customized to be shown in the right circumstances, for each kind of context, for every specific individual targeted as a valuable spot on the network. However, in Darfur, as in many other places and for the majority of people in the world, identities will still depend on co-presence, on who has to run and hide, and who is chasing and killing.

The concept of author, and therefore, of narrative creation, is present in some way or another in the analyses developed by Poster, Slevin, and Chandler. Either in the form of digital/analogue authors, bricoleurs in permanent transformation, or individuals engaged in a never-ending process of self-formation, the result is an unstable identity, an identity that, within the higher socio-economic segments of the world, has taken off from the platform of the "I am" to the atmosphere of the "I'm being." The concept of narrative embedded in this analytical view of the self, however, is not that unfamiliar from the traditional reality of humans as subjects experiencing - and building - the history of their lives. The additional element brought by the Internet, is the possibility for individuals to project their hi-story and frame it in a certain way. But narratives have to do, certainly, with a conscious author, and individuals using the Internet do not approach it as authors but as people that incorporate the medium to their real life, and use it to project that life, or at least certain pieces of it, to others. This mediated action and its results are not simply another story, nor a story-building attempt, but the experienced life of unconscious authors and unconscious audiences.

In RL clothes, accents, and expressed knowledge are ways in which we try to convey information about ourselves to others. Less clothes and more intimate shared information means that different subjects might be getting closer and closer, it means that there was enough compatibility to further the relationship. Web pages might be seen as representing this same "spectrum of revelation and knowledge". Some pages are formal and include basic information; others are more intimate and include every possible interest, movie watched or personal icon adored. I think it is an attempt to network with people at the ¿closer¿ more intimate side of the spectrum, an attempt to avoid the perceived waist of time of the transition from first contact to sexual contact, an attempt to show immediately the superficial essence of the postmodern-schizophrenic-self, in a world where no contact can be made with the individual next door, in a world where only speed and size matter.

====================

3) Is the internet a powerful democratizing force? (Week 7: a Contribution)

The concept of the Public Sphere is the face of a theoretical normative framework - a homogeneous space of embodied subjects in symmetrical relations, pursuing consensus through the critique of arguments and the presentation of validity claims (Poster, p. 181). The question of its applicability (potential existence, even) then has to be assessed according to what reality shows. Within the Greek-Roman-Christian tradition, the Public Sphere ideal seems positive, rational and beneficial for the world, a world of dialogue, understanding, and care and interest for the other. But reality shows something different, even in the so-called western democracies. A real space of heterogeneous groups and individuals, extreme asymmetries of power and wealth and opportunities, decisions based on elites’ interests pushed by corporate lobbying pressures, uncritical acceptance of reality, and invalid wars against everything in the name of freedom and peace. A reality that seems far away from spreading communicative competence and ideal speech situations. The world operates in a chaotic sphere at best, more and more with individualistic ideals and indoctrination based on private wealth, eternal growth, and lack of interest for other’s fates. And these ideals are far away from the Habermas dream, which is definitely not a priority in the ideological promotion agenda of Governments or Corporations.

Technology, however, offers certain opportunities for improvement, and as Poster, provocatively affirms, for structural change. The Internet carries two characteristics that make it really different from previous media channels. First, it contains massive amounts of information that give the users, literally, infinite choices within every information genre (news, academics, sports, places, pornography, fashion, music, people, etc); this characteristic involves aspects of fixation and participation of the technical medium of transmission, as developed by J. B. Thompson and Jim Slevin. Second, it facilitates to the extreme a pattern of media transmission unavailable for regular users until the 1990’s: that of some-to-some messages across time and space; this characteristic involves the technical aspects of reproduction, transmission direction, and – again – participation.

One-to-one media patterns were typical of “analogue” mail services or telephone calls. The one-to-many media pattern is typical of state or big corporate media, with more or less restrictions in time/space (film, press and magazines being more restricted than TV or radio). One-to-many media was promising: powerful mass communication offering support for education and the Public Sphere (specially in the format of European public broadcasting systems). However, these promises did not materialize fully. One-to-many media offered just a few choices to users, and even Habermas has moaned the demise of the Public Sphere ideal caused by commercialization, economic concentration, and the natural attraction that audiences feel to easy-entertaining content.

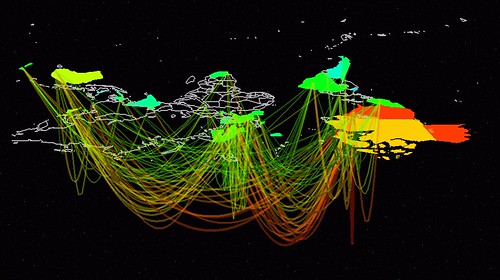

The mixture of these two characteristics of the Internet (infinite choice and some-to-some communication clusters) generates (in the McLuhan’s sense) a user that is obliged to learn to choose among, and create (in the non-technological-deterministic sense), infinite threads of information. The result is a permanent learning feedback loop where personal functional and hedonistic improvement is a priority, where information brand loyalty becomes unfixed-mobile loyalty, and where each user (powerful or weak) receives, sends, and accepts “some-to-some” communications, from and to several preferred clusters of related users, across several information genres, and across time-space. This information landscape is promising (again) and appears to offer an opening to diversity of opinions and to independent critical communications outside the mainstream media and social flows but with a strong potential to influence them both (Slevin’s Internet and Society Intensified Reflexivity concept).

Even when considering the digital-economic divide, it is a fact that the Internet is giving the traditional “powerless” a new sophisticated voice for new sophisticated struggles. The 31st December Women’s Movement of Ghana, The Gatsby Marketing Centre, and The Bombolulu Project, as described by Slevin (p. 211-213), or the Zapatista movement in Mexico (as described by Castells in The Power of Identity) are examples of new empowerment, social reflexivity, and group agency using technology. These new struggles are beyond the labor movements of the industrial revolutions, beyond May 1968, beyond the so-called western democratic systems tensions, and, as Poster proposes, even beyond the Public Sphere framework. These new sophisticated struggles are the postmodern versions of domination and resistance between leaders and followers whose relations are now mediated by the clustered-some-to-some logic of cyberspace and late modernity media systems. The eternal struggle, once again, but this time, between cosmopolitan leaders and cosmopolitan followers experiencing not dual but plural identities, plural lives, and plural hearts.

Choice and infinite availability of information, as provided by the Internet, and the new type of user that matches that combination, should be powerful supports for the deliberative model of publicness, based on legitimate decisions generated by processes of generalized deliberation (Slevin, p.186). If people actually take the decision of “deliberating” about an issue, the Internet will help to enrich such a process, with more information and opinions about it. In this sense, the Putin broadcast is not new, and there was no difference with old-fashioned telephone surveys on newscasts or phone calls from voters to political debates TV shows. However, the 24,000 questions show the “infinite” information characteristic of the Internet, with clusters of concerns or themes potentially emerging. Of course, they have to emerge freely (and be summarized without thematic discrimination) – without filtering – for the civil servant (Putin) to appreciate the main threads, or at least to be able to chose some of them without any editorial pre-selection. Systematic denial or exclusion of certain subjects would alert the users that were interested in those issues, potentially starting a process of communication with other users about such exclusion, unveiling hidden political intentions from the part of the medium, or the civil servant. Not addressing certain concerns impedes further deliberation about them in their relationship to the politician. Hiding “controversial questions” or leaving them unanswered, breaks the possibility to further deliberative arrangements within communication processes. It is in this sense that the Putin broadcast was closer to the traditional one-to-many media pattern than to the postmodern some-to-some plural media-scape.

Dahlberg’s paper about Minesotta’s E-democracy offers a very interesting case study of best practices for coordination and support of political debate based on the Internet. Several characteristics of this political experiment strengthen it potential: a precise balance of “flexible” rules; focus on specific themes that bind together the participants through the issues’ connection with everyday reality and concerns; strong support and promotion of respectful behavior; and the “unconscious” implementation – in a higher or lower degree – of the six Public Sphere conditions (autonomy from the powerful; critique of moral-practical validity claims; reflexivity; surfing on the others’ shoes; sincerity; inclusion/equality). This mixture, this process, guarantees a permanent formation/improvement of opinions held by the participants, with resulting decisions that should reach the best possible balance between arguments of policy and arguments of principle.

In December 2004 the Foreign Relations Ministry of Colombia found out that the Internet could be a useful tool. They created a Yahoo Group called Estudiantes Colombianos en el Exterior with the intention of linking up the 20,000 or so Colombian students across the world, learn what their concerns are, and facilitate their return to Colombia in good labor conditions. The moderator of the group is a bureaucrat with an office in the Ministry back in Colombia (there’s no independence from the government). Messages with controversial subjects like one I tried to post about the Cocaine problem (an article that was published in Amsterdam on the International Students news letter) was not approved by the moderator (exclusion of controversial themes). The group has had three discussions so far (5 months) which triggered many postings: one about how students see the country from the outside; a second one about the quality of the education in Colombia – triggered by a Colombian on-line newspaper article; and the third one about the focus of the group – should it be dedicated exclusively to students’ issues or should it include political debate about Colombian issues (politics in Colombia obviously include concerns about the civil war, the cocaine business, internal displacement and refugees, and all the social problems derived from this “nice” mixture). For this third discussion the moderator created a survey for people to vote – so far it seems that people want to include the political debate. I agree. People (4 or 5 postings) have started to complain that there is too much talk and not so much walk in the “community.” But from a communication perspective there’s already a process of opinion exchange and formation, and that generates already some walking at least.

My personal experience with the group was of interest in the beginning - I made a new friend that lives in Madrid also interested in the cocaine problem; then the postings began to be repetitive and long, so my visits decreased rapidly; finally, when my posting (400 Hundred Words on Cocaine) was censored I stopped posting altogether and only drop by to lurk occasionally. I sent the moderator the link to the Minnesota E-Democracy paper by Dahlberg as my last interaction.

So far I don’t feel that the group offers much utility for me when compared with my interests and with other Internet destinations. The group is not focused, and the postings I’ve read don’t really attract me to personally contact the senders. Still, I learn from observing the on-line Colombian behavior: all our traumas, our class driven selves, our denial and ignorance of the Colombian problems, our lack of reflexivity.

In any case I’ll be around that web neighborhood. Hopefully, the increasing interactions within the group will generate permanent thematic improvement and focus, opinion formation, inclusion and assessment of the key Colombian issues, and learning for all. All of them, effects that will spread to other geographic destinations in the World… and in Cyberspace.

====================

4) Literature:

SOME PARTS OF THESE TEXTS - DOESN'T REALLY MATTER WHICH ONES - ARE BASED ON THE FOLLOWING SOURCES (PLUS OTHERS NOT REFERENCED HERE):

Castells, M. (2001). The Internet Galaxy. Reflections on the internet, business, and society. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Castells, M. (2003). The Power of Identity. London: Blackwell.

Castells, M. (2001). The Rise of the Network Society. Reflections on the internet, business, and society. London: Blackwell.

Dahlberg, Lincoln. Extending the public sphere through cyberspace: The case of Minnesota E-democracy. FirstMonday. 1 March 2001.

[WWW-document].

URL: http://www.firstmonday.dk/issues/issue6_3/dahlberg

Giddens, A. (1999). Tradition. BBC Reith Lectures.

Giddens, A. (1999). Tradition. BBC Reith Lectures.

[WWW-document].

URL: http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/static/events/reith_99/week3/week3.htm

Peralta, C. (2004 - 2005).

Peralta, C. (2004 - 2005).

[WWW-document].

URL: http://nocomunicado.blogspot.com/

Poster, M. (2001). What's the Matter with the Internet? University of Minnesota Press.

Rheingold, H. (1999). Community Development In The Cybersociety of the Future. BBC, 1999.

Poster, M. (2001). What's the Matter with the Internet? University of Minnesota Press.

Rheingold, H. (1999). Community Development In The Cybersociety of the Future. BBC, 1999.

[WWW-document].

URL: http://www.partnerships.org.uk/bol/howard.htm

Slevin, J. (2000). The Internet and Society. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Slevin, J. (2000). The Internet and Society. Cambridge: Polity Press.