Controversial Issues: Negotiated Positions, Distant Ethics

A critical paper about the use of communication strategies in the current global ideological struggle between Corporations and Social Movements. The tension is exemplified here by Du Pont and Greenpeace, by Nike and the Anti-Sweatshop organizations. Two case studies are developed - within the specific theoretical perspective of Communication Ethics - in order to understand the tactical-strategic similarities and the distant ethical frameworks of the confronted actors and, therefore, the basic positions from which their actions towards the public are triggered.

1. Introduction

Today reality seems to be just an appearance. The more knowledge humans gather the more uncertainty there is. Ethics, values and norms used to be firm social standards, at least from the point of view of every type of society. The expansion of advanced capitalism and the emergence of postmodernity in the rich world created a huge intellectual movement that has developed theories about relativism, multiculturalism, and social constructions, and although each one of these schools of thought has distinct developments and research implications, they do share a common concern, or better, common doubts, about the nature of reality. A reality that in other times, and for the majority of people in the western world, was fixed and taken for granted.

Today, the schizophrenic behaviour of societies (Jameson, 1991) and the evident differences between different types of communities, as seen everyday through the mass media, show the absence of a common reality through which people can make sense of undeniable events like mass murders, post-modern wars, and human misery. But at the same time, all of them are rarely tangible events and they usually appear just as flashing fleeting images on high definition TV sets.

When ethical frameworks have to be built or analyzed within this post-modern vagueness they become controversial, and any ethical conclusion is always victim of the fact of being socially constructed and relative to the place and circumstances in which it was defined. Conclusions, however, are not random results; they are decided, as it has always been, but now in a global scale, depending on who is in power. On the other hand, the possibility to build social ideologies and to challenge taken for granted norms is an open door to new realities, changes and cultural options.

When this theoretical link, between present and potential realities, between old and new norms or ethical frameworks, is applied to contemporary corporate objectives and controversies, it is possible to find and describe the ideology behind corporate capitalism and the new values that contemporary agents of change and resistance are trying to implant and spread in society.

The present paper is an attempt to understand the ethical frameworks, and the practical behaviours and communication strategies developed by two opposing groups: corporations and social activists. This exploration of the actions and beliefs of both groups is based on a literature review of theories and case studies covering ethics and controversial issues. Different schools of thought were explored, and an up-to-bottom model to understand the structural relation between ethics and applied corporate and activists’ tactics was developed.

The research question that this paper attempts to answer is:

Is a common ethical field possible between corporations and social activists, a common field for agreement, where conflicting-controversial issues can be solved?

This question is framed in the field of corporate communication since “public controversies” between companies and activists are evident only when communications (and subsequently, mass media messages and then public attention) are involved.

In order to answer the research question two literature fields will be covered, one related to ethical and normative research and the second focused on controversy research and case studies.

I will first explore the ethical theories and trends in order to understand the types of values that have been observed and developed by researchers from different schools of thought. Secondly, the values behind the two opposing actors that are the object of analysis (corporations and social activists) will be analysed. Third, case studies about controversial issues will be used to illustrate the types of conflicts that corporations face and how activists try to put those issues into the public domain.

Finally, the theories and examples are the materials used to develop a vertical model that illustrates the way in which corporate and activists’ values relate and oppose to each other, in a social dynamic that includes public communications, political consensus building and ethical differences.

The present analysis will be covering issues and trends which are related to what is generally known as “the western world” (a.k.a. western democratic world; a.k.a. rich/developed world) and the regions it influences directly with its capitalist ideology, usually addressed as “emerging markets” or “developing countries”. However, huge regions and billions of people in Africa, Asia, Latin-America and eastern Europe, could not be considered part of this analysis, since even god has forgotten them.

2. The Ethical Issue in the field of Communication

The Association for Communication Administration – a professional body created to advance the development of the practice and research of communication within the academic field – agreed, in 1995, on a definition of the field of Communication that includes the “promotion of effective and ethical practice of human communication” (Johannesen, 2003, p. 205).

On a more theoretical approach to communication ethics, and in a further development from the Habermas’ concept (and book) of Communicative Action (which involved concepts of justice and solidarity), James Mackin develops a basic ethical principle stating that “individuals should support the communicative ecosystem that supports them. Supporting the ecosystem, however, does not mean blind loyalty to the way things are, but includes building, maintaining, and remodelling the system” (Johannesen, 2003, p. 203).

These two approaches, professional and theoretical, show the centrality of the “ethical issue” within the Communication Sciences. They show the belief among scholars (since Plato) that human communication processes involve matters of ethics, that is, of human conscious choices about means and ends of communication (what and how to say and with what intended or unintended function), communication choices that will produce impacts on others, choices that are subject to judgements of degrees of moral right or wrong (Johannesen, 2003, p. 202).

3. Ethical Trends in Communication Science

But if the ethical issue is central, what are the trends spreading from it to the world of social sciences and specifically to the field of communication? Richard L. Johannesen (2003, p. 205 - 215) has reviewed seven ethical trends from diverse schools of thought that are being applied to communication studies and research.

3.1. Media Ethics

This trend is related to the meta-concept of “ethical mutualism”, a balance between individualism and communitarianism, egoism and altruism, religion and science, rationalism and emotivism, legalism and consequentialism, absolutism and relativism. But this middle “balance point” seems to be more inclined to a communitarian ethic that includes a dialogic self, community commitment, civic transformation and mutuality in the organizational culture.

Applied to communication practices, this trend involves concepts such as humanness, truth telling, fairness, freedom, stewardship, impartiality, objectivity, neutrality, and corporate responsibility. The trend is aiming at building civic communications.

3.2. Individual and Social Ethics

The premise of this trend is the individual as a moral agent that has to decide between right and wrong while potentially receiving dissonant influences from his or her social space. Individuals are not wholly discrete, unrelated, atomistic entities; they live in a social context in which they are morally involved and at the same time, they’re still individuals, to which responsibilities are distributed within a community or organization.

This approach is, again, inclined to find the balance between the individual and the responsibilities attached to living within a community.

3.3. Freedom and Responsibility approach

This trend is in the same line as the previous one. Freedom clashes with ethics to gain more flexibility and individualism. Ethics conflicts with freedom to supplant personal licentiousness with social concern.

The pre-conceptual ethical frame here is that we are free not because we are detached from others but literally because we and them are interconnected. We are responsible, not in order to avoid harming others, but because we and them are mutually involved in one another’s completion as human beings and in sustaining the very social world that makes our life and its values even possible to consider.

This trend coins the word “rightsabilities”, a western version of the yin and yang of eastern cultures.

3.4. Organizational Communication Ethics

This approach is based on descriptive and normative ethics research. It involves ethical duties – guardedness, accessibility, non-violence and empathy – and social/organizational ethical practices – reflexivity and directness in problems solving, responsible interaction, structural integrity, sharing purposes and directions, valuing different perspectives, and personal integrity.

This trend has been inclined to research and application within the organizational context.

3.5. Feminist Communication Ethics

This approach emerges from the opposition to the tradition of rhetoric-as-persuasion (considered as representing a male-violent conquest-conversion mentality). A “womanization of rhetoric” is developed in order to establish a non-hierarchical, non-judgemental, non-adversarial framework, aiming at an equal, respectful and appreciative interaction within social contexts.

Ethical norms like trust, mutuality, justice, inclusiveness, participation and reciprocity are the touchstones for ethical communication relationships within this feminist ethics trend.

3.6. Ethics of care

The traditional ethic of justice characterizes the male moral voice. Individuality, autonomy, independence, judgement of competing rights and the search of judged equality and fairness.

The ethic of care characterizes the female moral voice. Relationships and interdependence of self and others, compassion, empathy, and nurturance help resolve conflicting ethical responsibilities to all concerned, including the self.

This trend, which includes a feminist outlook, contrasts with the male liberal tradition of rationality, rules and morality based on justice, liberty or equality. The ethics of care involve consensus instead of hierarchical decisions.

3.7. Virtue/Character Ethics

This ethics trend is based on the concept of virtues, as deep-rooted dispositions, habits, skills, or traits of character that incline persons to perceive, feel, and act in ethically right and sensitive ways. The assumption of this approach is that in moments of crisis or uncertainty, decisions stem from our formed character more than from deliberation.

The set of virtues driving ethical responses come from different social dimensions. The Judaeo-Christian culture: courage, temperance, justice, generosity, truthfulness. The feminist school of thought: care, compassion, nurturance and facilitation of growth and change, and love. The dialogical approach includes: authenticity, inclusion, confirmation and presentness.

Communication based on this approach should reach the truth, avoid bias and manipulation, avoid harm to others, serve the public, invite criticism, treasure trust and be accountable.

In summary, all these ethics trends aim at the well being of the self and the others, at expanding respect, understanding, cooperation and reciprocity. Within the communication field, only professionals that keep and live through these virtues will be able to improve the profession and to guarantee, through their work in the media, advertising, public relations or corporate communications, a positive influence in society, and a self-regulating professional environment that will be able to control manipulation, biased and false information, and unbalanced power flows[1].

4. Conflict in reality: Corporate and Activist values

If we were to describe the values in which the western corporate world is based the identification of them developed by Pirages and Ehrlich in 1974 would perfectly describe the social ideology of the neo-liberal present (Dee & Murphy, 1996, p. 2-3). The Dominant Social Paradigm (DSP) that the North-West has implanted across the world for the last five hundred years has finally evolved into an ideology that includes the following values:

· A belief in abundance and progress

· A devotion to growth and prosperity,

· Faith in science and technology,

· Commitment to a laissez-faire economy, limited governmental planning and private property rights.

This dominant social paradigm, which is supported by the multinational companies and their friends at the top of governments, could be renamed as “Anti-Ecological DSP”.

But such a model is being increasingly challenged by different kinds of movements[2]. This paper will be focused in exploring the values of two of those movements: the Social Justice movement [3]

and the Environmental movement. These activist groups are important for this analysis because they were born in the North-West and because their main target is the corporate ideology, its values, and its ethical contradictions.

4.1. The Environmental Movement values

It is the Environmental movement the one that has developed, in a consistent way, an alternative social paradigm opposed to the dominant one. The New Environmental Paradigm (NEP) is formed around such concepts as limits to growth, a steady-state economy, preserving the balance of nature, and rejection of the anthropocentric notion that nature exists solely for human use (Dee & Murphy, 1996). This “environmental vanguard” is trying to lead their fellow citizens to a new social paradigm, the NEP, project that requires a change in the fundamental values of society. On the other hand, the rear guard, society’s establishment and business elites would defend the old dominant paradigm (DSP), since that’s in their best short-term, short-sighted interests.

Ten new values synthesize the New Environmental Paradigm:

· Love and respect for nature

· Concern for public goods in contrast to an emphasis on private goods

· Cooperation over competition

· A concern for a minimum standard of living for everyone

· Careful planning to avoid risks in the production of wealth

· Conservation for resources for future generations

· A long-term view (a social psychology of glacial time[4].

· Environmental protection over economic growth

· Environmental protection over the provision of jobs

· Emphasis on energy conservation

A very different type of society will emerge if these Environmental Principles continue to be accepted and applied by more and more people. They demand not only an extensive change in policies, but also a metaphysical – or epistemological – mutation (Monbiot, 2004), which will affect basic economic, technological and ideological structures.

4.2. The Social Justice Movement

A less proactive movement, since it exists based on its opposition, or reaction, to global corporate capitalism, is the Social Justice Movement. This highly diversified, highly networked movement is attempting to establish (or re-establish) the control of society over its institutions after the failure of traditional democratic controls under the conditions of globalization of wealth, information and power. This objective is product of the movement’s radical critique of the mechanisms of political representation in the institutions of global and national governance. The following four characteristics offer a general definition of the Social Justice movement (Castells, 2004):

· It is a diversified movement involving a wide spectrum of nodes with different and specific agendas. From critical-moderate social reformers to anarchist anti-capitalists, all are bind together by the opposition to the current globalization process, which is based on an asymmetrical economic liberalization that fits the interests of corporate capitalism.

· Its power has emerged from its intensive and conscious use of the Internet, and from its grassroots–network communication strategies. The movement sees the Internet, and its underlying “networking” concept not only as an organizational tool but also as the emergent form of a self-managed society.

· It is a combination of powerful ideological and active nodes based in open societies, which usually correspond to the (so-called) developed countries, and networks that reach out through a planet in which most people suffer oppression and poverty. In this way the movement challenges globalization on behalf of the whole of human kind.

· Although its name has been coined using the prefix “Anti”, and in spite of being addressed and known by the public opinion as the Anti-Globalization Movement, it is not a movement against globalization, but a movement for participative (as opposed to representative) democratic globalization, based on the new ideals and decision-making processes that are part of the emerging global network society.

When the Dominant Capitalist values are contrasted with the Environmental model, or with the critiques and claims of the Social globalists, the main contradiction of the corporate ideology emerges: the dominant values, the short term objectives, the corporate fundamentalism and all its self-confident rhetoric, will be worthless if there is no world, no land, no earth, no humans to experience and exercise those values.

5. Controversy: case studies

Especially for the last three decades, corporations have been enduring the attacks of these activist groups. Issues related to environmental crimes, human rights violations, labour oppression, corporate economic concentration and consumer rights, have made it into global news with names of big companies attached. Shell, Coca-Cola, McDonalds and Nike are the most prominent examples of these controversies. Corporations have responded in a number of ways, including the deployment of massive Public Relations strategies. In the following section two case study controversies are analyzed with the specific objective of finding and understanding the communication strategies and challenges that each of the opposing actors face, and illustrate through the case studies how each actor’s strategy is designed to support and expand each actor’s interests/values.

5.1. Greenpeace Corp.: A conflict scenario

Although the Environmental movement is very diverse, composed by different factions with different countries of origin[5], it is Greenpeace the one organization that has achieved worldwide brand awareness thanks to its media tactics. Nevertheless, those tactics are, to some extent or another, at the core of any other group within the movement, shaping the objectives, the controversies and the negotiations in which the environmental groups are involved, usually opposing major corporations.

The hate-hate relationship between Du Pont and Greenpeace that climaxed between 1988 and 1990, is a good example of the dynamics of activists-corporations controversies, the values behind them, and the strategies used by each actor to gain public support, avoid government regulations, or take advantage of the opponents weaknesses.

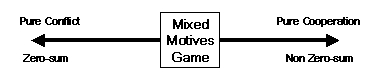

The strategies of Public Relations related to conflicts and controversies, according to different scholars (see Dee & Murphy, 1992), can be placed on a spectrum (model) that varies from pure conflict to pure cooperation. This variation also reflect strategies based on Zero-sum and non-Zero-sum outcomes for the actors involved (a model based on Games Theory). Every conflict has to be solved (if possible) through a bargaining process between the parts. The negotiation zone (if it exists) is the Mixed Motives Area of the Game. See Figure 1:

The history of this conflict-relation goes back to the 1980’s when the destruction of the Ozone layer became an issue and Greenpeace began to target Du Pont. The corporation was listed as one of the top polluters in the world. Du Pont’s industrial processes release the chlorofluorocarbons (CFC) that destroy the ozone layer. Du Pont began to invest in actions oriented to look as, and to be, an environment friendly corporation. By the early nineties Du Pont had invested as much as $145 million to develop alternatives to CFCs. Until now, the Environmental issue has been one of the weak points for big companies in different stakeholder fronts (public, government, employees, shareholders and activists).

The specific demands of Greenpeace could be summarized in two points: stop CFCs altogether; and inform the public about the environment and health harms that CFC and its replacements cause. By 1990, these demands would have implied to Du Pont an investment of over $1 Billion, which the corporation (and its shareholders) were not willing to pay. But they were willing to negotiate with Greenpeace and to develop further environmentally friendly actions that could be communicated to the different publics. This strategy was focused to proof Du Pont as a progressive-open but strong company. A non-zero-sum strategy.

Greenpeace, on the other hand, was focused on pursuing its goals (specific changes in Du Pont industrial operations and in the quality and quantity of information it distributes to the public) with the self-imposed condition of not compromising its radical determination to protect the environment “right now!” In fact, this “radical position” developed by Greenpeace has been one of its key communication and operational strategies for entering the collective mind of individuals and for taking the environmental issue to the public opinion arena.

Greenpeace radical position implies three particular game strategies with concrete consequences for the development of negotiations (Dee & Murphy, 1992, p. 10):

· Extreme Actions: with the objective to attract media attention and build public awareness.

· Unilateral Demands: as proof that the Environment is first and foremost, beyond any corporate negotiation attempt.

· Intolerance for compromise: radical unwillingness to negotiate and to cede any points even in the interest of generating dialogue with the other party.

These three components of the Greenpeace strategy constitute a clear Zero-sum approach to the conflict. A position at the extreme “Pure Conflict” side of Figure 1. The question then is why is Greenpeace using this extreme strategy – which is also general within the organization approach to other controversies with other corporations?

Organizations strategies are dictated by the characteristics of the organizations’ members and by their external target audiences. In the case of Greenpeace, their internal and potential constituents are radical activists committed to the New Environmental Paradigm, strongly oriented to action against polluters, and as a public they are not only proactive information seekers but highly aware, concerned and involved with the environmental issue (Dee and Murphy, 1992, p. 11).

The external audiences, on the contrary, are indifferent, passive people, with low-involvement in terms of information seeking and very much unaware of the environmental issue. For this target audience the long-term survival of the planet is a minimal inconvenience when compared to their day-to-day problems. The result is that the public that Greenpeace targets, which is “in charge” of building public opinion, is not really interested in the issue of Environment.

Another key external public for Greenpeace is the Media. The Media is needed to distribute the information in order to get more and more people aware of the issue. Access to media personnel and to media exposure is conditioned to extreme competition with hundreds of other happenings in the world. This structure has to be confronted by Greenpeace all the time if any message about the environment is to be sent to the general public.

The three strategies used by Greenpeace have been designed to influence each of these target groups in a direct way. Extreme actions, unilateral demands, and radical commitment, constitute the way to attract new members-activists that relate and identify with the Greenpeace approach to the environmental struggle. The combined strategy, specially the extreme actions and the potential of conflict escalation, is the way to attract the news media professionals, always slaves of the pseudo-events and the tragedies, and take each Greenpeace battle/project, hopefully, to the front pages. And once the issue makes it into the news, the public begins to develop, to increase, or to maintain, an environmental concern, which in practice tends to be very superficial since the media very rarely covers the environmental issues in depth, but nevertheless, that superficial public concern becomes the building block of public opinion on the Environment, with the potential of putting serious pressure on corporations’ practices and/or of bringing government regulation or a government arbiter into the conflict (the ultimate fear of any corporate agent involved in this type of disputes).

Du Pont, on the other hand, has different goals. When facing a crisis with escalating potential, corporations want to avoid two things: a negative impact on their brand image and new costly regulations from government bodies. These two effects might generate a loss in the company’s shares value, and both are enough reasons to use all the strategic tools at the company’s disposal to neutralize the crisis. The rule here is that companies will show greater willingness to negotiate when issues groups can attach economic or legislative penalties to corporate uncooperative behaviour (Dee and Murphy, 1992, p. 13) or when the company is Business-to-Consumer driven. Greenpeace activist leverage carries the potential of this kind of penalties for any company and Du Pont’s marketing strategy, in spite of not being precisely business-to-consumer, is strongly linked to its public brand awareness.

During the protests against Du Pont in the early nineties, the company’s approach to the conflict was a mixed strategy composed by:

· Punitive measures like arrests of demonstrators during their “extreme actions” (e.g. climbing of industrial towers, accusatory big-format billboards, and blockage of roads leading to the factories) and reiteration of Du Pont’s own industrial policy/position.

· Conciliatory messages to Greenpeace and to Greenpeace’s uninvolved target audiences – media, legislators, general public / consumers – stating that the corporation was investing on environmental solutions and was willing to negotiate with the activists.

The location of Du Pont on the conflict spectrum illustrated on Figure 1 would be a varying point between the pure conflict extreme and the “negotiation/conciliatory zone”. The result of this mix or variation strategy was effective for the company.

On the one hand, Greenpeace actions didn’t get the attention, exposure or sympathy from the media that is essential for the organization’s objectives. Much of the media items covering the demonstrations and actions were isolated at the level of local media in the towns where the attacked factories were based. Reasons for this negative outcome for the environmentalists vary from media personnel rejection of Greenpeace actions (and the organization in general), to activists’ mistake of using Du Pont’s nylon materials in their “protest billboards and climbing equipment”, to conflict of interests between the environmentalists’ objectives and local populations depending on Du Pont factories as major local employers.

On the other hand, Du Pont managed to get a coverage of the situation in which the punitive actions against the activists (arrests, charges and repressive police actions) were justified as measures to control extremist-radical activists, and in a parallel move the company conveyed their corporate concern for the environment with communications targeting the public to show Du Pont’s new policies and real investments (independently of their magnitude) in environmentally friendly technologies and industrial processes.

This particular dispute between Greenpeace and Du Pont, with the combative “obligatory” tactics of the activists aiming at a “reversal of industrial trends”; and the company’s issue communication strategy based on the best practice of “informative, non-threatening, direct and fair” messages to the public in order to legitimize its “functional industrial substitutes” approach, had an outcome of an isolated Greenpeace unable to beat the “mixed-cooperative” approach of Du Pont, and a nice collaborative image for one of the worlds top polluters.

In spite of this positive/negative result for this or that party, according to Dee & Murphy (1992, p. 17), this “game was ultimately about getting the attention of important audiences, a goal that made prolonged conflict a central strategy” for each side. A game that, even considering potential future negotiations, has its real origins in the confrontation of two different sets of values: a rearguard value system not really concerned with the future of the planet and its inhabitants, and a vanguard one which seriously believes that the world can be saved.

5.2. Nike and its labour practices: communication strikes back

The struggle of the Social Justice Movement (a.k.a. Anti-globalization movement) is mainly focused in the opposition to the asymmetrical economic liberalization that fits the interests of corporate-transnational capitalism. One of the main objectives of this opposition is a more egalitarian distribution of wealth and power in order to stop poverty and to give people, especially the poor, more opportunities and more agency, that is, more control over their own destiny (Zen, 1998).

In the context of this struggle, and especially in the battle to take the objectives of the movement to the media and to make people aware of the conditions that motivate the movement, communication and “public relations” strategies are primary for the global justice activists. The use of symbols and of strategies to encode those symbols as messages for the targeted receivers is part of the plan of every activist campaign. Symbols of power, of unequal power that is, are permanently used to make the campaigns more attractive for the media and for the public. Major corporate names like Shell and Coca Cola (involved in obscure human rights violations in Nigeria and Colombia respectively)[6], McDonalds (a powerful black hole within the global food culture), and Nike (the sweatshop champion); their logos; and their market positions; are always used by the activists for stating the critiques and claims of the movement, claims and critiques which in practice are applied to these companies but in theory apply to the whole neo-liberal corporate system as well.

Obviously, many companies, competitors of Shell & friends, in their respective industries, could be also subject of such movement critiques and actions. Why is it then that the above-mentioned companies are always used to exemplify the global justice statements? The irony of the answer is that it is their business and marketing success what makes them the ideal target. Every movement’s action using those “power names” is leveraged by the very idea that makes those companies successful towards the eyes of the public. Their brand, their brand name, their brand logo become part of the opposition against them.

Nike’s case, related to sweatshop practices in so-called developing countries, illustrates well the communication dynamics and the ethical issues involved in the tensions between activists and corporations.

The Social Justice movement is decentralized in thousands of nodes and works as a network [7]. This means that different movement’s actors – NGO’s, labour unions, religious groups, and others – are permanently scanning their environments to detect potential weaknesses within corporations’ practices. Issues like cultural rights, human displacement due to new industrial plants, pollution, and labour rights might become the thorn on the side for a company. Nike was spotted as a labour rights violator, and was positioned as such by the movement in what can be called a form of “counterbranding” or “counterpublicity”. But how is such an oppositional strategy built and how does it work?

First, the industrial trend in which a company is basing its processes (and its inherent potential for abuse of employees, communities or environment) has to be spotted and understood by the movement, beginning with one or more nodes within its global network. In Nike’s case, the industrial trend is a specific variation of the outsourcing practice: the “Export Processing manufacturing system”, where production for a brand is contracted out to companies based in newly industrialized countries (Korea, Taiwan, etc.), which have their factories in low-wage countries in the, so-called, developing world (Knight & Greenberg, 2002).

Second, different nodes from the movement’s network begin to collaborate investigating companies that match the industrial model and checking for abusive practices or for paths of negotiation to achieve better standards for the actors involved. This research implies, many times in a global scale, facts checking; contact with different sources like company stakeholders and company insiders, some of them hostile, others interested in the movement’s objective; and proofs gathering. Although the Nike’s anti-sweatshop case developed since the early 1990’s, an important climax was reached in 1997 when a company employee leaked an audit report by Ernst and Young about a factory in Vietnam that was incurring in serious threats to workers’ health and safety while manufacturing Nike products.

Third, coordinated communication and publicity campaigns – press and video releases; contacts with key journalists; Internet documenting – are developed in different regions of the world, to generate exposure of the issue. The media is attracted to the controversy precisely for the same reasons that it is attracted by Nike’s self-branding events. Nike’s position as a celebrity corporation attracts media attention and functions as an information subsidy (for different types of media, Nike’s events information reduces the costs of producing content and Nike receives free media space in exchange). But the activists also use the “information subsidy” strategy to attract the media towards negative information about the company.

This strategy exploits Nike’s own dependence on public image and marketing communications, turning the Nike’s brand image back on itself and opening up issues as wages, working conditions, and worker rights to ethical criticism. The branding (promotionalism) reflexivity, as Knight & Greenberg (2002) call this reverse effect of brand power, is the emergence of a power flow that does not come from the elites but from below. This form of non-elites power is called Subpolitics. Knight & Greenberg use Habermas’ theory of communicative action to explain the concept: “if politics represents the intervention of the system, that is, the state and market economy, in the everyday life-world of lived social and cultural experience, then subpolitics represents the reciprocal feedback effect of the life-world on the system.”

The climax of this tension was reached on May 1998, when Nike CEO Phil Knight announced in a press conference that “new initiatives to further improve factory working conditions worldwide and provide increased opportunities for people who manufacture Nike Products” would be developed and executed by the company.

In contrast to the Du Pont/Greenpeace case, Nike’s strategy to counter the attacks from the movement has been rather clumsy. That is not to say that the company has suffered as much as “its” workers in the so-called developing world. But given the marketing expertise and success of Nike, its issue management (or PR) strategy has been far from positive. Here’s a short chronology (Knight & Greenberg, 2002).

· In the early 1990’s when the attacks about labour abuses started the company avoided the issue by blaming its contractors.

· From 1993 to 1996 Nike denied the problem pointing at its own code of conduct as enough proof of its good corporate behaviour.

· In 96-97 big labour scandals in the US (involving several “big ones” companies) put the labour issue back to media attention and reports of Nike’s “intermediated” labour abusive practices were aired, and its audit reports criticised by the media, by scholars and by activists.

· The 1998 Phil Knight press conference marked the beginning of a new strategy (including responsibility acceptance and some real labour conditions improvements).

The current strategy of the company is using two dimensions, and it’s more in line with Du Pont’s approach to confront Greenpeace, although with its own particularities and implied differences:

a) Nike’s auditing initiatives, its social responsibility and philanthropic programs, and other educational or fitness programs are being executed in the so-called third world as a marketing tool. On the one hand the company demonstrates its good intentions and responsible behaviour, on the other, tries to get media attention about this positive developments and connect them with its brand image.

b) Counterattacking and criticising the activists as misguided and misinformed idealists. This is a reflexive tactic targeting the movement’s communication strategy.

This controversy-game is heavily inclined to be played on the media and marketing field with the main difference being the direction and intention of the messages (up-down/down-up; direct/reflexive), and indeed, the values behind each player strategy. The values of the new social groups-nodes that make up the networked Social Justice movement are not about the immediate, short-term satisfaction and material self-interest of those who are part of the organization, but are values embedded on an altruistic dimension and oriented toward social solidarity and to promote the well-being of others. From a north-western perspective the movement’s values are the base for a fight on behalf of others; others that might be unknown and live at a distance, but who are enduring the abuse of the corporate system, an entity which is culturally and geographically more proximate (Knight & Greenberg, 2002).

6. Conclusion: The resulting controversy model

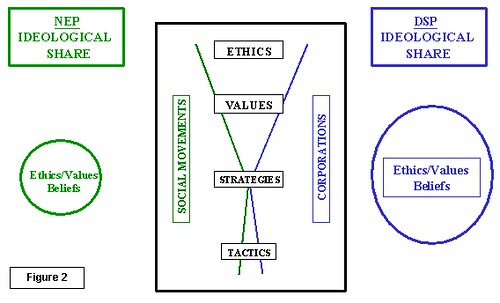

After reviewing the ethical trends originated from different schools of thought, after exploring with some depth the ideological values in which Corporations and Activist movements are basing their actions, and after checking the dynamics of controversy through the Nike and Du Pont case studies, it is needed to summarize the dynamics – that go from ethical belief-systems to concrete social actions – that constitute contemporary conflicts/controversies between corporations and activists? Figure 2 illustrates a proposed “controversy model” resulting from the present analysis.

From a macro level perspective the abstract positions of ethics and values corresponding to the opposed groups are basically different. They are structured on different epistemological frameworks. At the strategic level the similarities between the opponents could be closer, not only because the communication and media strategies each side uses can be the same, but also because it is at the strategic level that the decision to negotiate can occur, reflecting a practical and real point of (temporary) controversy resolution. At the level of tactics, that is, specific actions for specific situations differences appear again (although with a smaller divide) illustrating how corporations on the one hand, and activists on the other, execute their actions at a given time in a very different way (both might use Television to reach their targeted publics – strategy – but each one will execute a totally different communication campaign or event on that specific medium – tactic).

The opposition between the two sides reflects an ideological struggle in which each side is pursuing a specific social agenda. An agenda that implies influencing, convincing, and educating the society – through strategies and tactics – according to each group’s objectives. This struggle is generating an “ideological (political) share” for each group, with different segments of society choosing sides or, at least, choosing some values or ethical dimensions within each side: this means that the model also works at the individual level, within each person (an individual process of transformation into supporting some, or all, of the ideas and values of the opposing sides). The activists’ ideology, as represented in this paper by the environmental movement and by the Social Justice Movement, currently holds a smaller political share than that of the neo-liberal ideology, represented by the corporations.

The “ideological share” in the model can be also seen as a “market share” between the corporate fundamentalists and unaware individuals, and moderate or humane companies and interested citizens for which maximization of profits and consumption benefits won’t be as important as the maximization of the well being of their stakeholders (employees, communities, environment, etc) and/or their fellow men and women.

If the neo-liberal machinery is not able to proof that its value structure will indeed bring prosperity, environmental sustainability and dignity/decency to the lives of billions of people, the world will become an even more chaotic and painful place. So far the Dominant Social Paradigm has been unable to deliver, opening the political space to its opponents due to what is increasingly viewed by many as serious failures in its ethical/value structure. The trend for the future will be the intensification of the struggle in the media and in the political arenas.

The social activists’ agenda, on the other hand, does match the ethical trends presented here. It is an attempt to generate positive social outcomes with an ideology of communitarian interaction and cooperation and without the emphasis on individualism and self-interest that has characterized the market fundamentalists’ paradigm.

The challenge for the activists’ movement in its direct confrontation with the corporate world implies a real ideological change in corporate stakeholders’ minds (as primary targets) and the public; and the expansion and improvement of their strategies (including their communication campaigns) in order to change the social paradigm. At the same time, the change is opposed by current economic trends that favour more concentration of power and resources in fewer hands and the homogenisation of cultures around the world

This social/ideological game is indeed performed on the strategic stage. On it, two opposing players/ideologies interact. The potential result of that conflictive interaction between radical reformists and powerful reactionarists will not be a permanent agreement but constant negotiation and controversy; nor a common ethical field, but a gradual change toward a different and more humane world.

As Kingsley (1966, p. 13) rightly stated in his definition of the functions of controversy within the public relations field, expandable now to the ideological struggle for which human communication is essential, “controversy has an important function since out of it may emerge something approximating to the truth, or at the very least, what might be termed pragmatic, workable solutions to human problems.”

The communication field and its professionals, working for each side of the political divide, will have huge influence in the social developments that the ongoing global ideological battle will produce. For that reason the model and themes presented in this paper, and the way their different dimensions are expressed, should be kept as objects of further research and analysis.

7. References

· Castells, M. (2004) The Information Age. Vol. 2. Blackwell. 2nd Ed.

· Dee, J., & Murphy, P. (1992). Du Pont and Greenpeace: The Dynamics of Conflict between Corporations and Activist Groups. Journal of Public Relations Research, 4(1), 3 - 20.

· Dee, J., & Murphy, P. (1996). Reconciling the Preferences of Environmental Activists and Corporate Policymakers. Journal of Public Relations Research, 8(1), 1 - 33.

· Heath, R. L. (1998). New Communication Technologies: An Issues Management Point of View. Public Relations Review, 24(3), 273 – 288.

· Holtzhausen, D. R., & Voto, R. (2002). Resistance from the Margins: The Postmodern Public Relations Practitioner as Organizational Activist. Journal of Public Relations Research, 14(1), 57 - 84.

· Johannesen, R. (2003). Communication Ethics: Centrality, Trends, and Controversy. Communication Yerabook 25, pp. 201 – 235. W. B. Gudykunst / ICA.

· Jameson, F. (1984). Postmodernism, or, the cultural logic of late capitalism. London: Verso.

· Kingsley, R. E. (1966). The Function of Controversy: Neutralization is Not the Goal. The Public Relations Quarterly, 7 – 13.

· Klein, N. (2002). No Logo. New York: Picador.

· Knight, G. & Greenberg, J. (2002). Promotionalism and Subpolitics: Nike and Its Labour Critics. Management Communication Quarterly, 15(4), 541 – 570.

· Monbiot, G. (2004). The Age of Consent: A Manifesto for a New World Order. London: Harper Perennial.

· Zen, A. (1999). Development as Freedom. New York: Anchor Books.

=================

Notes:

[1] Such a professional has been identified by Holtzhausen & Voto (2002) as the postmodern communication practitioner. Their study is focused on the Public Relations field, but such a vision of communication professionals as organizational activists is potentially extensive to the other communication fields.

[2] In The Information Age, Vol. 2 (2004), Ch. 2, 3 and 4, Manuel Castells identifies and explores in depth seven movements (from a set of many others): The Mexican Zapatistas, the American Militia, the Japanese Aum Shinrikyo, the Muslim al-Qaeda, the Anti-globalization Movement, the Environmental Movement and the Feminist Movement.

[3] Monbiot (2004) uses this name. He clarifies the Social Justice movement has other names attached to it by different actors – media, activists, politicians, etc. The most famous of these is the “Anti-Globalization” movement. Other names coined are: Civil Society movement; Anti-Capitalist movement; World Democracy movement; Alternative Globalization movement; and Movement of Movements.

[4] Castells (2004) has identified three kinds of “time” concepts: a) Clock time: it corresponds to time as understood in modern industrial societies until the present: a time based on sequencing of events and predetermined schedules that rule human life; b) Timeless time: characteristic of the new network societies where the aim is instantaneity, time compression and short term demands for every social process, generating systemic perturbations and discontinuity in the sequential order of clock time; and c) Glacial Time: it is based on the Environmental Movement’s belief that the relation between humans and nature is very long term and evolutionary, that sustainable development means intergenerational solidarity, that the value of our life has to be measured by the types of lives that our children, and the children of the children of our children will endure or enjoy.

[5] Castells (2004) identifies at least six different factions or trends within the Environmental movement, each one involving a set of groups or ideological sub-trends: Group of Ten; Not in my Back Yard; Earth First; Ecofeminism; Greenpeace; and the German party Die Grunen.

[6] During one of the 2004 IDFA (International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam) debates, Naomi Klein, the author of No Logo, stated that companies such as Shell and Coca Cola should be strongly punished due to their relation with Human Rights violations against labour activists in Nigeria and Colombia. In Klein’s view these companies did not receive serious legal or social punishment after such unethical behaviours.

[7] The Global Justice movement network structure makes it more mobile and flexible than bureaucratic organizations. The anti-sweatshop movement, specifically, is composed by different groups that engage in diverse activities (culture jamming, conventional public protests, participation in shareholders’ meetings, and policy-regulation initiatives). The internet is increasingly the tool to coordinate or inform about this actions, a tool that seems to democratize corporate activist relations by diminishing the corporation’s gatekeeper role in the communication of critical information and by enabling a platform for dialogue, plus information about facts and opinions (for more on the Internet and Social Movements see Castells, 2004; Heath, 1998; Klein, 2000).